The forgotten explorer and his incredible legacy

Some of the extraordinary items in the Antarctic 3D Artefacts experience on the Trust’s augmented reality (AR) app, are from Carsten Borchgrevink’s Southern Cross expedition to the remote Cape Adare peninsula in the Antarctic from 1898-1900.

Although the names Scott, Shackleton and Amundsen may be more familiar when it comes to the era of historic Antarctic exploration, it was Carsten Borchgrevink and his crew who were the very first to establish a base and live on the continent. Borchgrevink had only limited formal scientific training but has since been acknowledged as a pioneer in Antarctic work, and a forerunner of the latter and more elaborate expeditions.

Carsten Borchgrevink grew up in Oslo and was a childhood friend of Roald Amundsen (who in 1912, led the first party to the South Pole). Before the Southern Cross expedition, Borchgrevink had been a surveyor and teacher in Australia and left behind a wife and six-month-old baby.

In 1894, he had previously landed at Cape Adare as a deckhand on a Norwegian whaling expedition, and also carried out scientific work there. This kickstarted his career as an explorer and prompted his desire to return to the Antarctic. His experience on the whaling crew enabled him to get generous backing for his Southern Cross expedition from English publishing magnate, Sir George Newnes, who invested £35,000, a staggering NZ$7.6 million today.

The expedition’s goals were to explore, contribute to science and look for commercial opportunities. The details were sketchy, but Carsten Borchgrevink and the nine members of his party from Norway, Britain and Australia, would spend a year in Antarctica, cut off from the rest of the world.

The Southern Cross sailed from London on 22 August 1898, and after a three-week break in Hobart, Tasmania, reached Cape Adare on 17 February 1899. With an average age of just 26, and little exploration or leadership experience, the men in Borchgrevink’s shore party faced a huge challenge in an unknown land.

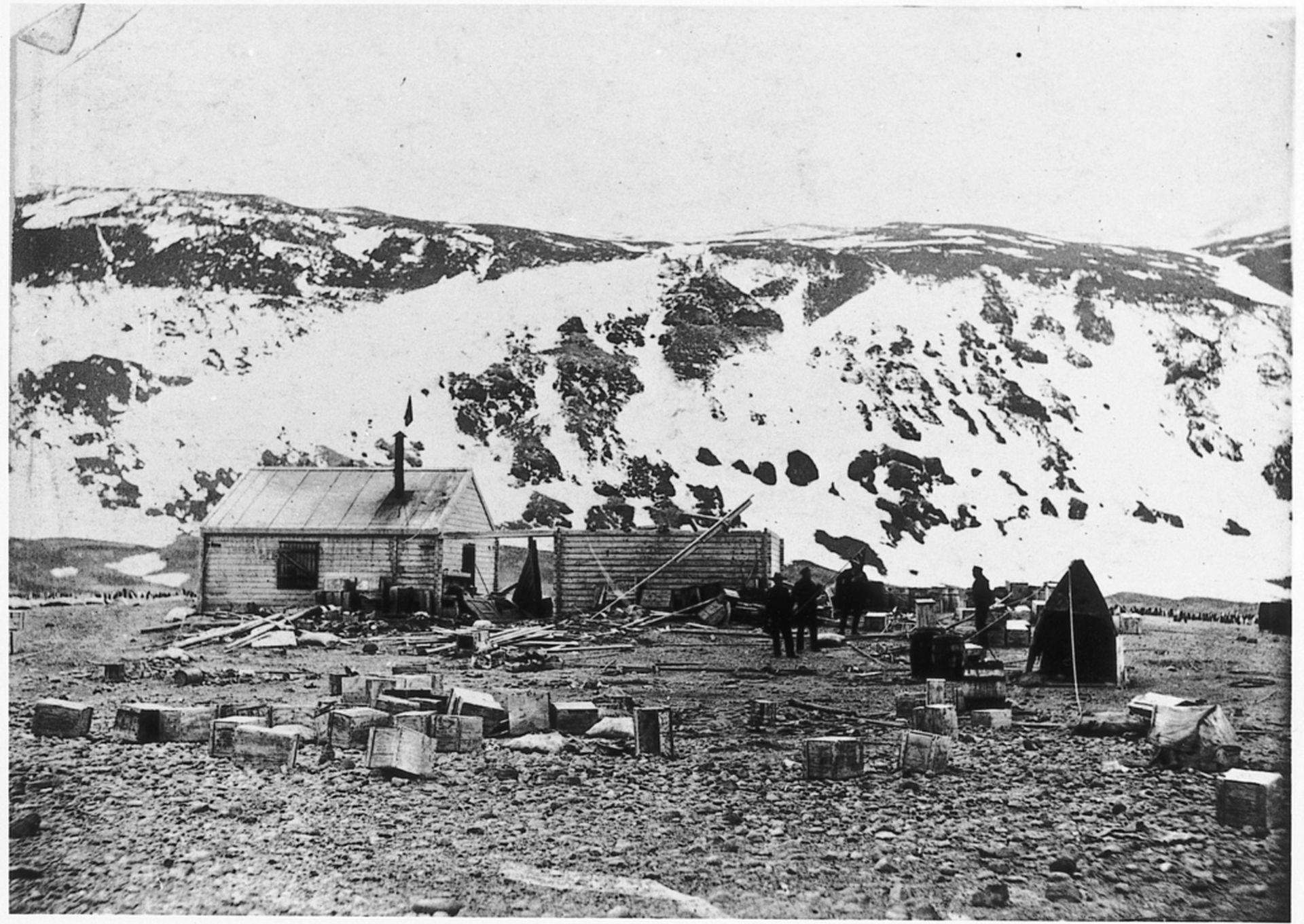

They erected two simple but strong prefabricated, pine kitset huts. A wooden frame covered with seal skins created a sheltered walkway between the huts and a lean-to for storage. Cables were slung over the roofs and secured to ships’ anchors buried in the ground to hold the huts steady in the wind. Each hut was about 25 square metres, with one used for stores, and the other for living accommodation.

Although Cape Adare turned out to be one of the harshest places in the Antarctic, these buildings have survived for more than 120 years in the wind-battered environment, making them some of the strongest on the continent.

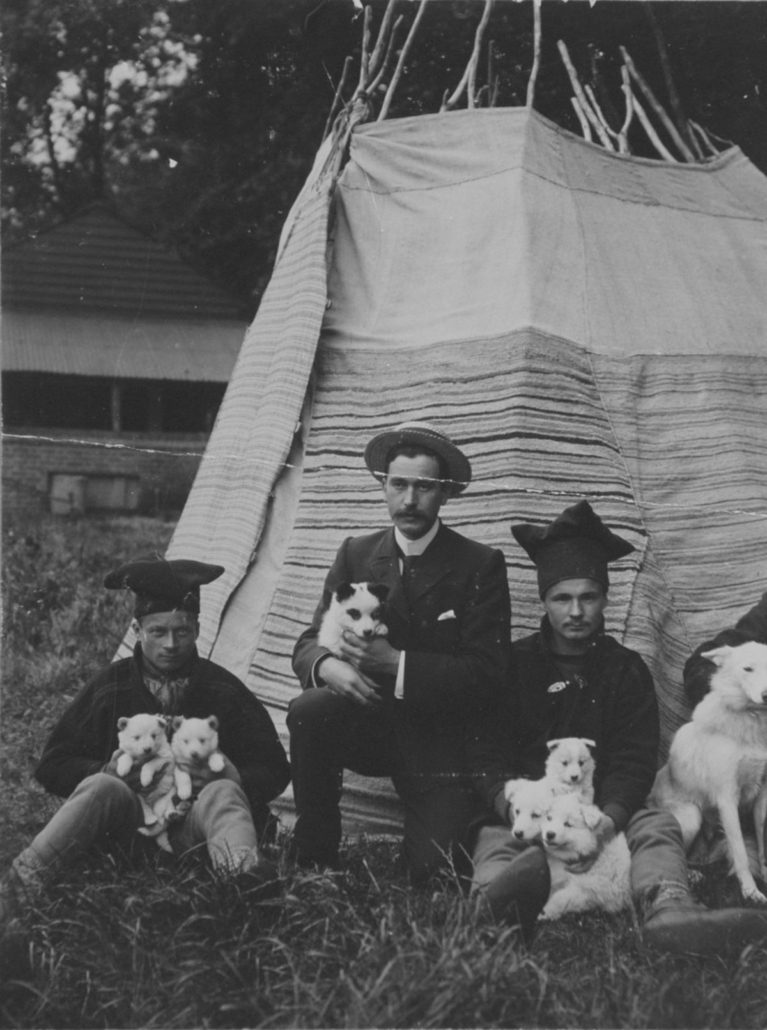

The Southern Cross was the first expedition to use dogs in the Antarctic, and they became an important part of exploration there for much of the twentieth century. Two young Sami men, Ole Must and Per Savio, from the far north of Norway, were on the Southern Cross expedition to care for and train the dogs. Their experience in cold climates and their skill in handling these half-wild animals were vital to the expedition’s survival.

Borchgrevink also pioneered the use of the Primus stove on the continent. It had been invented in Sweden six years earlier and would become a cornerstone of later Antarctic exploration.

There were huge challenges for the team during their year on the ice. Head zoologist, Nicolai Hanson died, a candle left burning caused extensive fire damage to a hut, and several members of the party were almost asphyxiated by fumes from the stove.

Bitter factions formed. The men were separated by language barriers and arguments about inconsistent decision making. As the weather worsened, so did the mood in the hut. Most of the men slept until noon and filled their waking hours with cards, chess and reading. Some improvised using the limited materials at their disposal, with a paintbrush made from penguin feathers, and a ball of string, thought to be made from dog fur, later found at the Cape Adare huts. Many of the men became adept at sewing, and some learned the basics of photography, with Southern Cross being the first Antarctic expedition to leave a full photographic record.

Almost every man on Borchgrevink’s expedition would later regret his decision to take part. Louis Bernacchi, the party’s Australian physicist wrote that a state of ‘democratic anarchy’ prevailed, with ‘dirt, disorder and inactivity’ the order of the day.

However, the expedition did establish several major Antarctic firsts which influenced the course of history for decades to come.

Borchgrevink’s team proved it was possible for humans to survive the Antarctic winter. Although they didn’t venture far, the men also learned valuable lessons about travelling in Antarctica, particularly how swiftly deadly storms can arise and how easily the sea ice can break apart, leaving travellers marooned. Under Louis Bernacchi’s leadership, the Southern Cross team collected a full year of weather readings. For the first time, scientists could track the seasonal variations in Antarctic sunshine, temperature and wind. Their data set the baseline for Antarctic climate science.

They also identified an access route onto the Ross Ice Shelf, which would become the starting point for the first journey to the South Pole.

When Southern Cross returned at the end of January 1900, Borchgrevink decided to abandon the camp, although there were sufficient fuel and provisions left to last another year. The Northern Party of Scott’s Terra Nova expedition in 1911 was the only other group to occupy the huts at Cape Adare.

The surviving dogs were quarantined at Stewart Island under the care of the Traill family, which later sold pups from the white Samoyeds, creating a line of pure bred Southern Hemisphere Samoyeds that exists to this day.

The reception afforded to the Southern Cross expedition on its return to England was lukewarm as the British public’s attention was already fixed on the forthcoming national expedition of which Robert Falcon Scott had just been appointed commander.

In 1902, Borchgrevink was sent to the Caribbean by the National Geographic Society to report on the aftermath of the Mount Pelee eruption. After that he settled is Oslo, mainly away from public attention. His pioneering work and contribution to polar exploration was finally recognised by several countries in the years that followed, with the Royal Geographic Society awarding him its Patron’s Medal in 1930. It acknowledged in its citation that justice had not previously been done to the work of the Southern Cross expedition.

Download the Trust’s AR app and explore some of the items left behind by these early expeditions to Cape Adare and see photos, videos and listen to audio about the explorers’ experiences and how the Trust’s team is working at site conserving these huts.

How to access the app

The app is available to download for free from Google Play or the App Store.

The application is only available on surface tracking Augmented Reality compatible devices,

visit our store pages on your device to see if your device is compatible