On 21 December, the heavily-laden Discovery steamed out of Lyttelton where tens of thousands had gathered to see her off. Scott recorded in his diary:

“It is most difficult to speak in fitting terms of the kindness shown to us in New Zealand … On every side we were accorded the most generous terms by the firms or individuals with whom we had to deal in business matters.”

As the Discovery headed southwards the expedition stopped at Port Chalmers for coal and to bury a seaman, Charles Bonner, who had fallen from the top of the mainmast as the ship left Lyttelton. On 9 January 1902, a call was made at Cape Adare where the record left by Borchgrevink was found, and on 4 February, during flights by Scott and Sub-Lieutenant Ernest Shackleton RNR in a hydrogen balloon named Eva over the Great Barrier (now called the Ross Ice Shelf), Shackleton took the first aerial photographs of Antarctica.

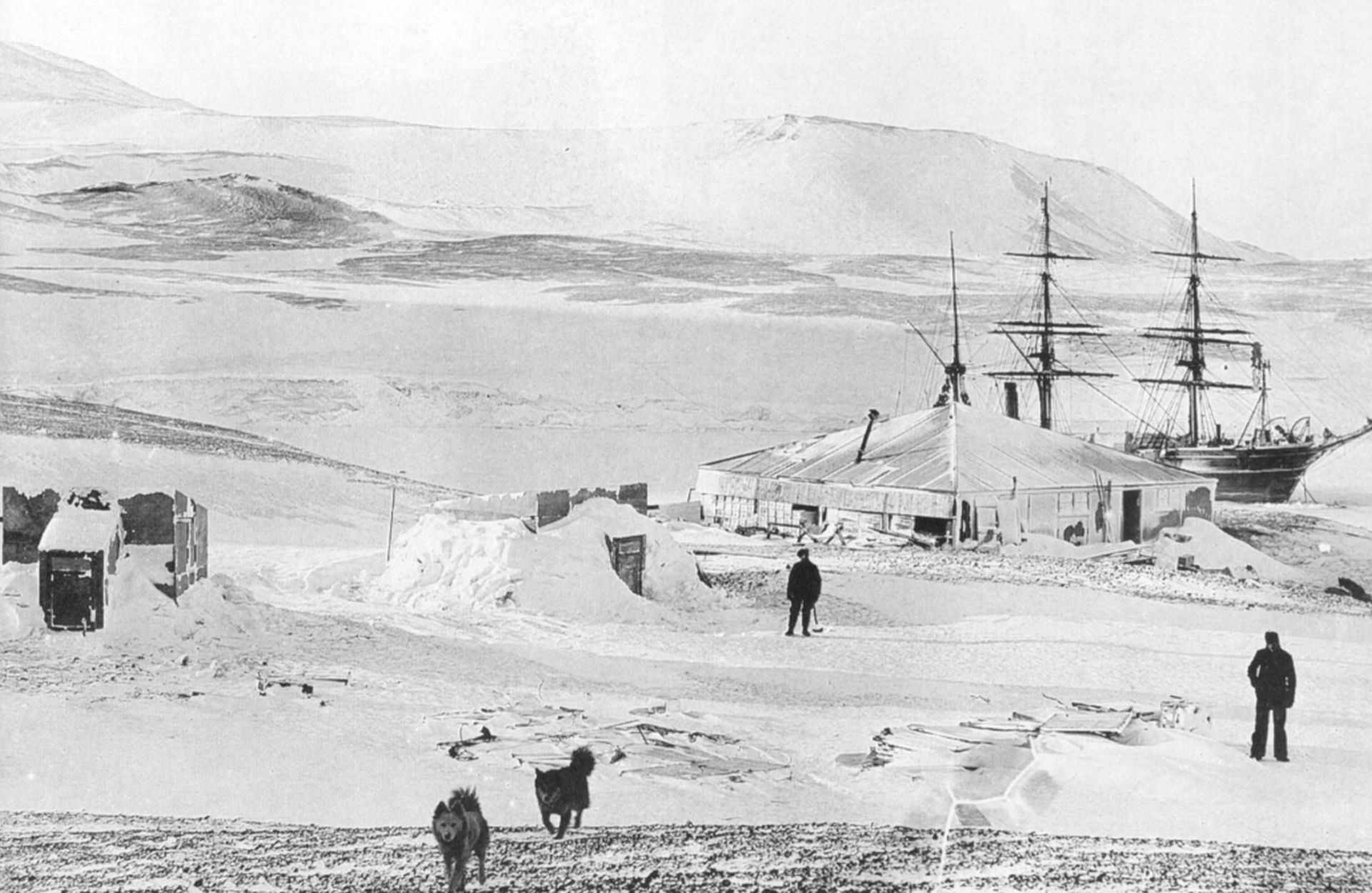

Granite Harbour on the western side of McMurdo Sound was considered a possible site for wintering, but Scott opted to winter over in what they named Winter Quarters Bay, a small indentation at the end of the Hut Point Peninsula on Ross Island and described by Wilson as “the most perfect little natural harbour imaginable”.

It had not been intended that the Discovery should winter in Antarctica but, instead, leave a small land party in the hut that Professor Gregory had designed. However, by 8 February, Scott decided to remain and the ship was secured to the icefoot. The Discovery was then frozen in for two years and became home for 47 officers and men, 30 of whom were from the Royal Navy, the others being a mixture of Merchant Navy and Royal Marine, along with five scientists and four civilians. On 11 March, however, their number was reduced by one when a young seaman, George Vince RN, died when he fell over an ice cliff returning to the ship in a blizzard and was never seen again.

Construction of the hut, some 200 metres from the ship, soon began. The ground was levelled, but owing to the permafrost a few centimetres below the surface, many hours were spent digging the foundations before Dailey, the carpenter, could erect the frame. The structural frame, including posts, beams and rafters, was infilled with prefabricated roof, wall and floor panels. Stencilled letters and numbers on the various parts facilitated construction. As with RE Peary’s winter quarters (later named ‘Anniversary Lodge’), erected in North Greenland in August 1893, the intention was to enclose the three sides below the edge of the verandah with provision cases, against which snow could accumulate.

By 8 March the hut was complete, with windows and skylights installed and the exterior may have been painted terracotta. Scott described the building:

“The floor occupied a space of thirty-six feet square, but the overhanging eaves of the pyramidal roof rested on supports some four feet beyond the sides, surrounding the hut with a covered verandah. The interior space was curtailed by the complete double lining, and numerous partitions were provided to suit the requirements of the occupants. But of these partitions only one was erected, to cut off a small portion of one side, and the larger part which remained formed a really spacious apartment.

We found, however, that its erection was no light task, as all the main and verandah supports were designed to be sunk three or four feet in the ground. We soon found a convenient site close to the ship on a small bare plateau of volcanic rubble, but an inch or two below the surface the soil was frozen hard, and many an hour was spent with pick, shovel, and crowbar before the solid supports were erected and our able carpenter could get to work on the frame.

“In addition to the main hut, and of greater importance, were the two small huts which we brought for our magnetic instruments. These consisted of a light skeleton framework of wood covered with sheets of asbestos. The numerous parts were of course numbered, and there would have been no great difficulty putting them together had it not been that the wood was badly warped, so that none of the joints would fit together without a great deal of persuasion from the carpenter.”

“The main hut is of most imposing dimensions and would accommodate a very large party, but on account of its size and the necessity of economizing coal, it is very difficult to keep a working temperature inside; consequently it has not been available for some of the purposes for which we had hoped to use it.”

![]()

![]()