THE BRITISH ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1910–13

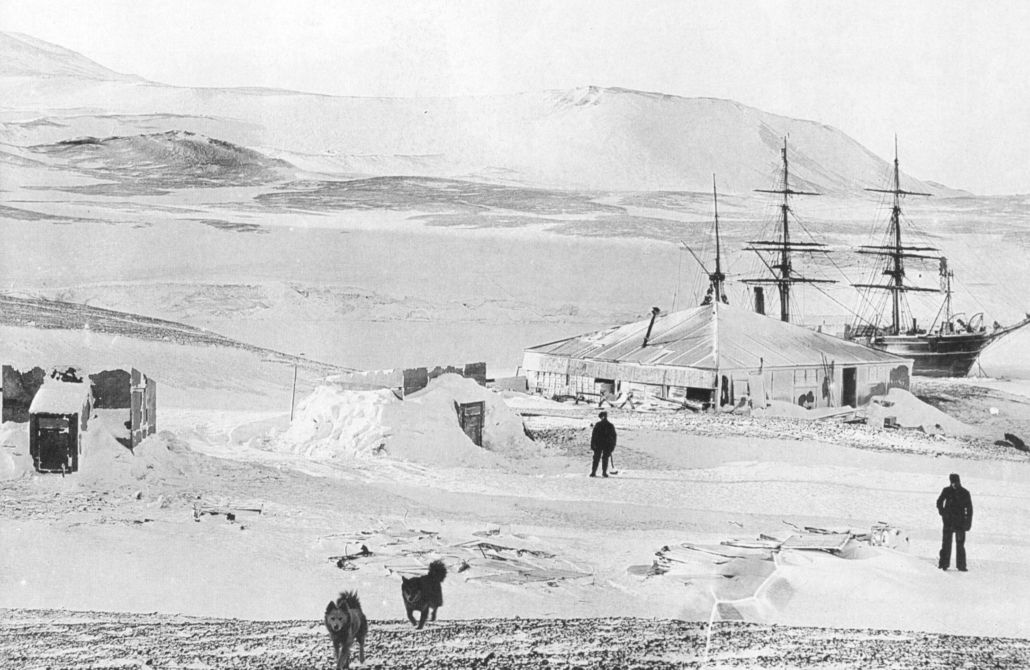

Like Shackleton, Scott had been obsessed with returning to Antarctica after his first journey and, by this time, was convinced that the Pole was his prize. He too had worked hard to raise the necessary support and he finally headed south again from London on 1 June 1910. On this second expedition, Scott planned an ambitious scientific programme, but the primary goal was to reach the Pole. He was using the Terra Nova as his expedition vessel, a ship that had served as a relief vessel on his first expedition, and he contemplated using Discovery hut for members of his wintering party in 1911. However, sea-ice prevented the ship from getting close enough to offload stores and, instead, he established his winter quarters at Cape Evans in early January 1911. On 15 January, Scott went with Cecil Meares to inspect the Discovery hut. He was not impressed with what he found:

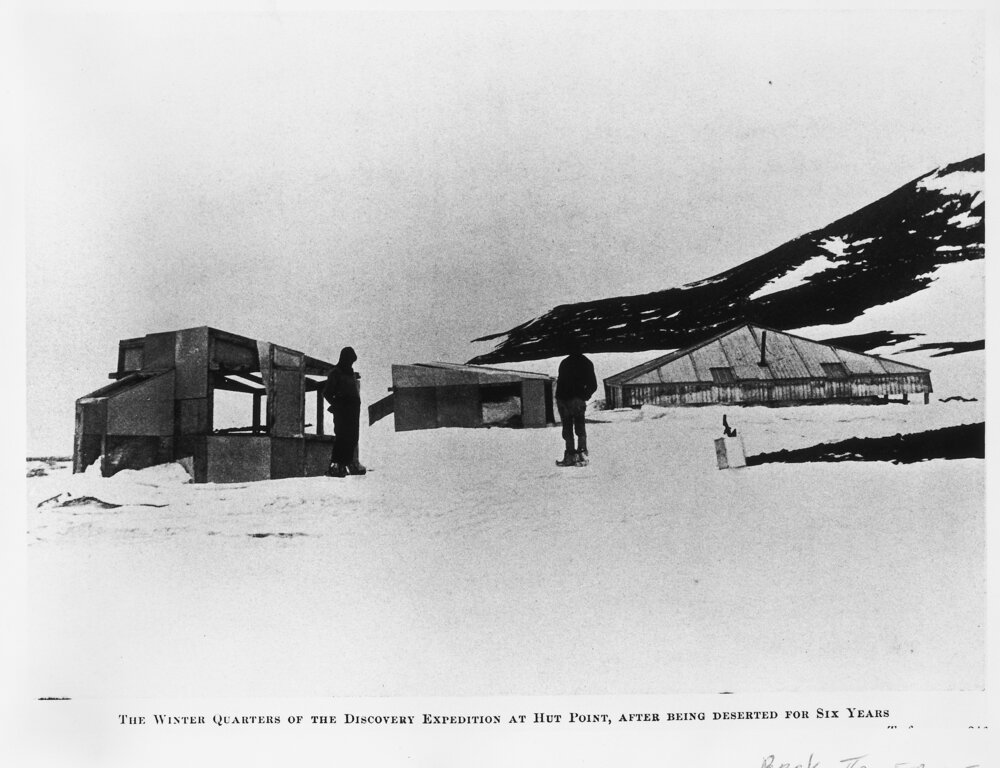

“On my arrival at the hut to my chagrin we found it full of snow. Shackleton reported that the door had been forced by the wind, but he had made an entrance by the window and found shelter inside … They actually went away and left the window (which they had forced) open; as a result, nearly the whole of the interior of the hut is filled with hard ice snow, and now it is impossible to find shelter inside.

“Meares and I were able to clamber over the snow to an extent and to examine the neat pile of cases in the middle, but they will take much digging out. We got some asbestos sheeting from the magnetic hut, and made the best shelter we could to boil our cocoa. There is something depressing about finding the old hut in such a desolate condition … I went to bed thoroughly depressed.”

Depot laying for the main southern journey began and the Discovery hut was again used as a staging post. In March, a party cleared the accumulated ice and snow and, using provision boxes, rebuilt the inner walls to retain warmth. Outside the hut, stables were built beneath the north and east verandahs with provision boxes, to provide shelter for their ponies. On 7 March, Scott wrote:

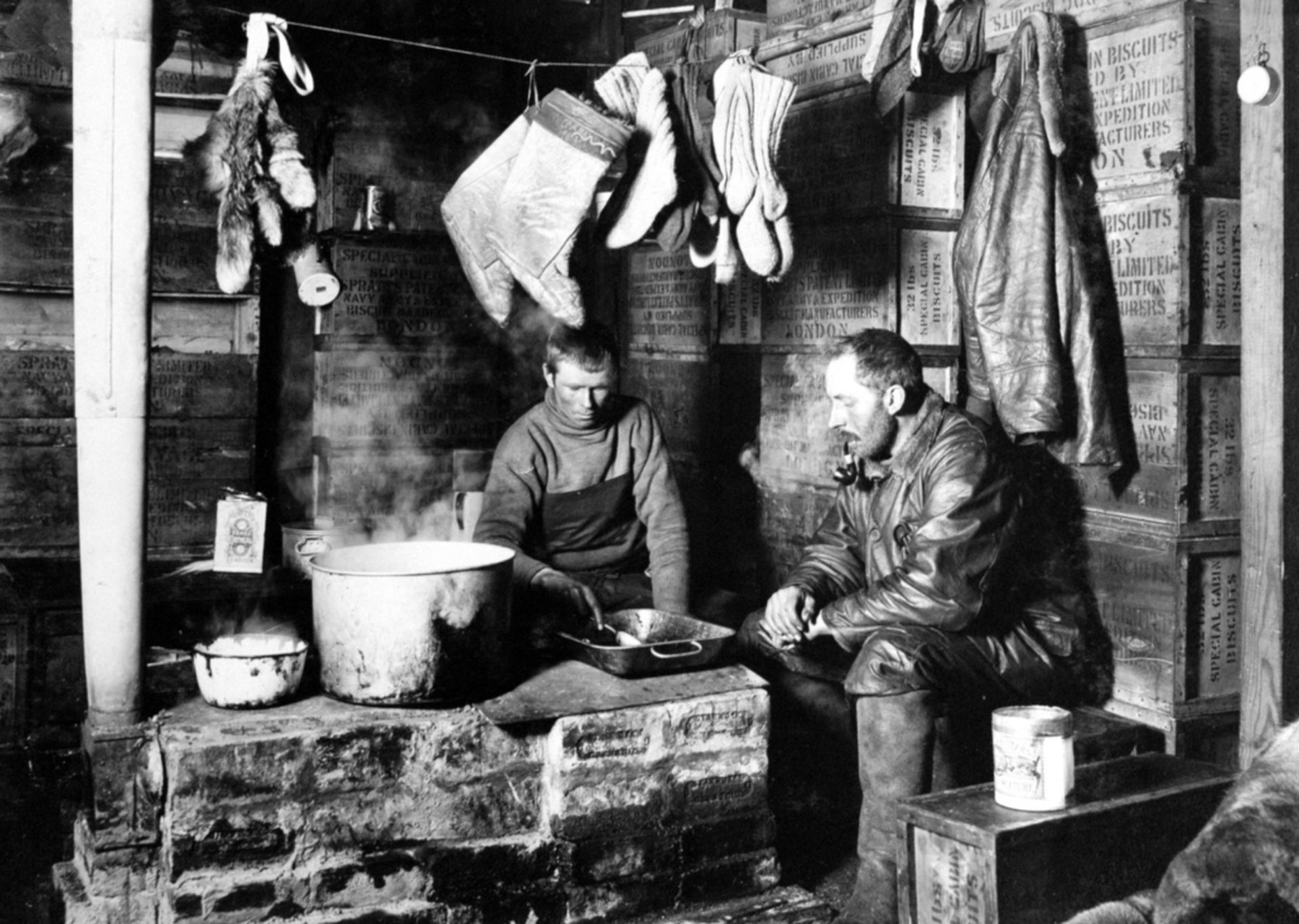

“We have made a large L-shaped inner apartment with packing cases, the intervals stopped with felt … The temperature in the hut is low, of course, but in every other respect we are absolutely comfortable. There is an unlimited quantity of biscuit … One way and another we shall manage to be very comfortable during our stay here, and already we regard it as a temporary home.”

The sea-ice was too thin to risk the trek back to Cape Evans so, to keep warm, Oates and Meares made a blubber stove that, according to Gran, was constructed with “two oil cans in which bricks are placed” and connected it to the old stove flue. Using some carbide they found, Oates and Gran then tried to make acetylene lamps. Wilson insisted that they test the gas first, however, the experimental lighting was almost a disaster. In Gran’s words, “mine blew up and nearly killed Meares, covered me with carbide, and created alarm and despondency in the hut. Perhaps Titus (Oates) will lose courage. If his blows up, the hut will go with it”.

Gran said, the hut soon had “a pungent odour of blubber and blubber smoke … the fireplace smokes unbearably”. By 9 March, fuel was becoming scarce and Scott noted the stove, “threatens to exhaust our store of firewood. We have redesigned it so that it takes only a few chips of wood to light it and then continues to give great heat with blubber alone”.

Old awnings were scavenged by Petty Officer Evans to line the sleeping quarters, and asbestos sheets were used to level the floor and to make pot lids. For warmth, some of the men slept around the stove. Three days later, when living conditions had improved, Scott added, “The hut is getting warmer and more comfortable. We have excellent nights; it is cold only in the early morning”.

With the arrival of the western geological party at Hut Point in mid-March 1911, there were 17 men living in the hut, more than at any other time. Use was made of Shackleton’s Plasmon biscuits, tins of Danish butter, peas and salt meat and, from Scott’s first expedition, cocoa and biscuits. On the night of 27 March, they had a hoosh made from ten-year-old peas and seal liver. With further work on the stove, and the use of additional pipes, there were no back-draughts and no smoke inside. On 13 April, the men finally decided to risk the journey to Cape Evans, travelling overland to the Hutton Cliffs then descending to the sea-ice and proceeding to Cape Evans.

In August, on the way back from their epic mid-winter journey to the Emperor penguin colony at Cape Crozier, Edward Wilson, Henry Bowers and Apsley Cherry-Garrard took shelter in the Discovery hut, erecting a dry tent they found inside and warming themselves with two Primus stoves.

With winter drawing to a close, sledging began on 1 September 1911 and numerous spring trips were made to Hut Point to depot supplies for the southern journey to the Pole. On one occasion, when Debenham and Cherry-Garrard were at Discovery hut, Cherry-Garrard noticed the interior was full of smoke. “We found that the old hut was alight between the two roofs. The inner roof was too shaky to allow one to walk on it, and so, at Debenham’s suggestion, we bent a tube which was lying about and siphoned water up with complete success.” Today, evidence of a fire is visible in charred wood about the flue.

In September, an aluminium telephone line was laid from a reel mounted on the rear of a sledge over the sea-ice from Cape Evans to Hut Point, and the first communication was made on 1 October. Five days later, Oates and three others took the ponies to Hut Point from where preliminary journeys were made to Corner camp. Scott, who arrived back at Hut Point from the Barrier on the 27 October and doubtless aware of the near catastrophe in early September, noted:

“Meares and Demetri have been busy, the hut is tidy and comfortable and a splendid brick fireplace had just been built with a brand new stove-pipe leading from it directly upward through the roof. This is really a creditable bit of work. Instead of the ramshackle temporary structures of last season, we should have a permanent fireplace which should last many a year.”

Five days later, the weather was so bad that they took the ponies inside, Cherry-Garrard writing, “three of them were housed with ourselves inside the hut, the rest being put into the verandah”. Next day they set out sledging southwards.

The various parties in support of the trek to the Pole returned to Discovery hut. In February 1912, the hut became a haven for Lieutenant Evans, who had contracted scurvy and was being cared for by Lashly. In April 1912, after food had been placed for Scott at One Ton Depot, Cherry-Garrard spent some time recuperating in the hut as, “blizzards raged periodically with the usual creakings and groanings of the old hut … the hut was bitterly cold with only one man in it”.

Meanwhile, Scott and his team had reached the Pole and were battling blizzards and starvation as they desperately tried to reach the safety of Hut Point on their return journey. Scott’s last diary entry is dated 29 March 1912 and, despite the attempts of Cherry-Garrard and Demetri to reach them, the Polar Party perished just 11 miles from One Ton Depot.

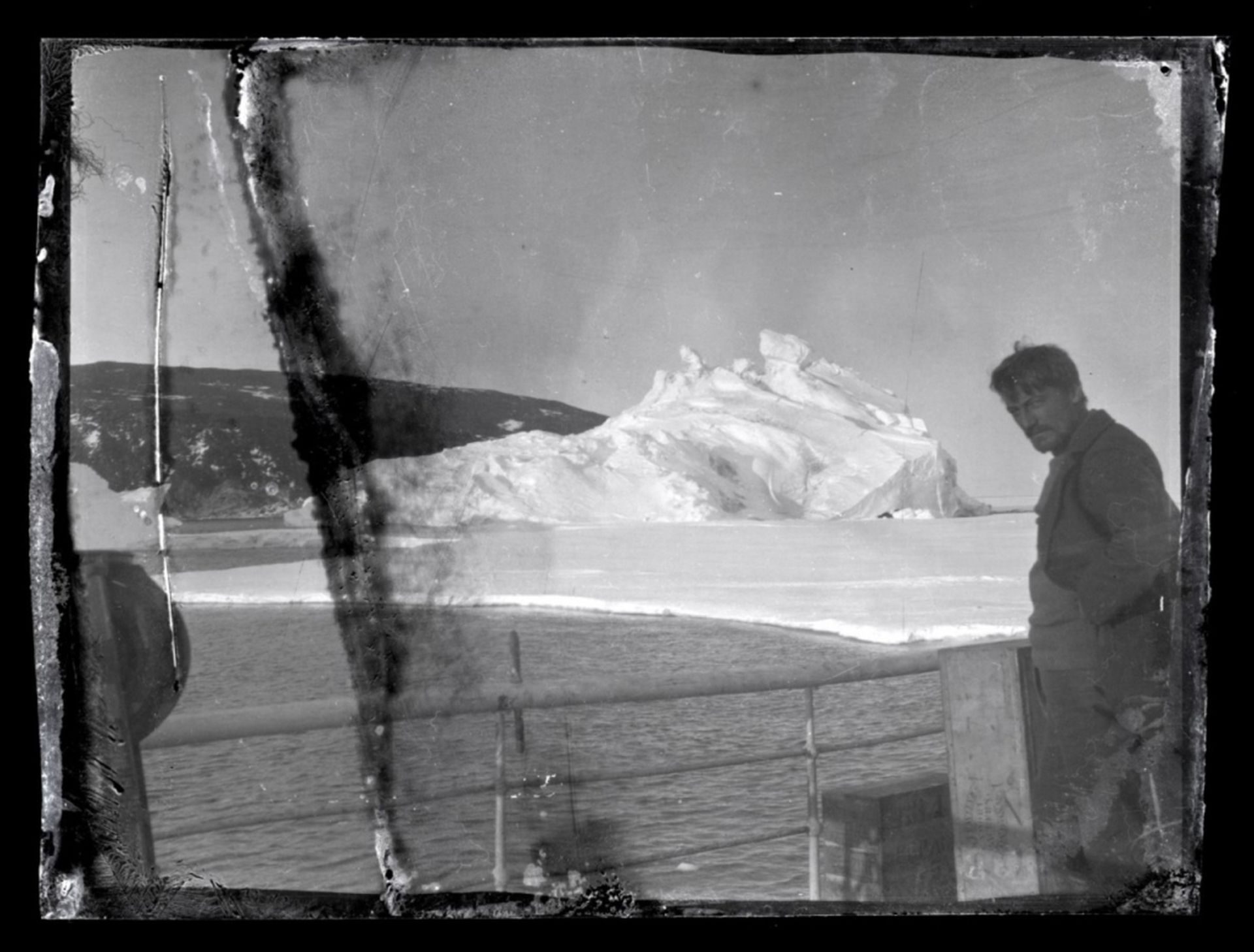

It was not until 1 May 1912 that the last team of the season left Hut Point for Cape Evans where they spent their second winter. In October, the search party of eight men with seven mules, which had been brought south on the second voyage of the Terra Nova, arrived at Hut Point. They located Scott’s last camp on 12 November. Six days previously, the Northern Party, led by Lieutenant Victor Campbell RN, had reached Hut Point after their epic winter stranded in an ice cave on Inexpressible Island. They had trekked down the coast, subsisting on seals and penguins, until they picked up a depot at Cape Roberts, crossing the sea-ice to Hut Point. Here, they received a message advising of the death of Scott and his party.

The final use of the hut by the British Antarctic Expedition was on 20–21 January 1913, when eight members of the expedition stayed. A large cross of jarrah, made on the Terra Nova, was painted white and the lettering in-filled with black paint and allowed to dry in the hut. Next morning, the cross was erected on Observation Hill, to the memory of Scott, Wilson, Bowers, Oates and Petty Officer Evans.

![]()

![]()