In the last years of the nineteenth century Antarctica must have seemed as remote and forbidding a place as space does today.

Only a few hardy travellers, whalers and sealers had ventured into Antarctic waters and, aside from mapping portions of the coastline, none of them had really explored the Great Southern Continent. The idea of spending an extended period of time in Antarctica, particularly the long, dark winter there, was something to be dreamt about by only the bravest, most driven – or most rash – explorers.

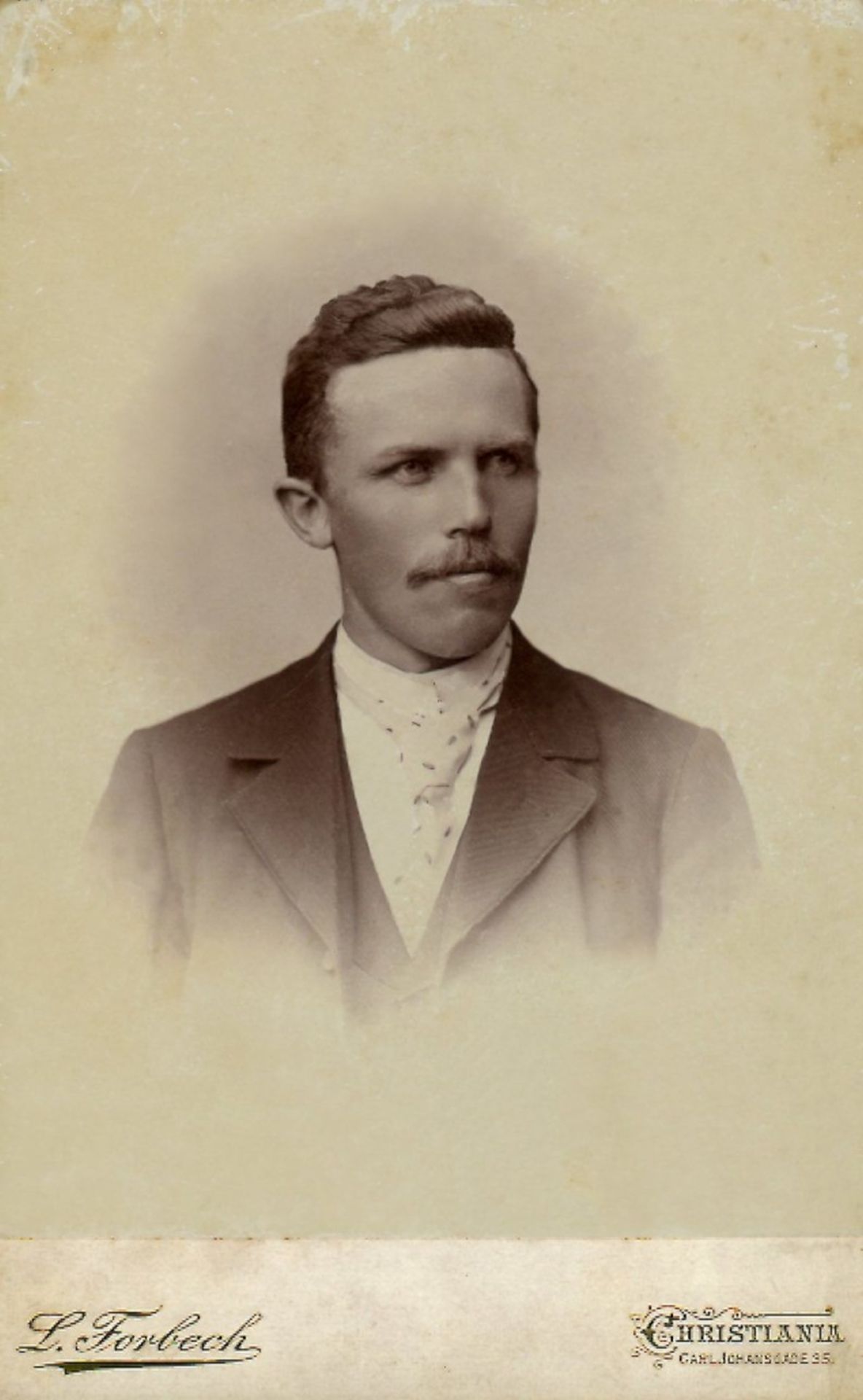

Carsten Borchgrevink, leader of the British Antarctic Expedition 1898–1900, was a man who embodied all three characteristics. Although not nearly as well known as Scott or Shackleton, Borchgrevink remains a key figure in Antarctic history.

Even though Borchgrevink’s expedition was marred by controversy and a measure of conflict, his team did make many noteworthy achievements. They conducted significant scientific and meteorological observations, mapped the Cape Adare region, made sledging journeys over the sea ice, and completed a ski journey to a point further south than anyone had previously reached. More importantly they proved that people could survive the long Antarctic winter living on the continent itself. The ten men spent the last winter of the century living in a tiny, cramped hut (with another hut for their supplies), perched on the edge of a narrow wind-swept spit, surrounded by towering cliffs at remote Cape Adare at the northern reaches of the Ross Sea. Today, those huts still stand on Cape Adare, making Antarctica the only continent in the world where the first buildings to be constructed still exist.

Cape Adare was first discovered by James Clark Ross in 1841, but, the real story begins with the momentous landing there on 24 January 1895, from the whaler Antarctic, an event that was to mark the start of the heroic era of Antarctic exploration. There are varying accounts as to who was first ashore, but Carsten Borchgrevink, who had convinced the captain of the Antarctic to take him on board in the combined role of seaman, seal shooter, skin curer and naturalist, recorded the moment as follows:

“I do not know whether it was the desire to catch the jelly-fish (seen in the shallows), or from the strong desire to be the first man to put foot on this terra incognita, but as soon as the order was given to stop putting the oars, I jumped over the side of the boat, I thus killed two birds with one stone, being the first man on shore, and relieving the boat of my weight, thus enabling her to approach land near enough to allow the captain to jump ashore dry-shod.”

It would seem Borchgrevink’s claim was somewhat optimistic because there is some evidence that there had been at least five earlier landings in Antarctica by sealers. Regardless of who made the first footfall, the visit ignited an enduring desire within Borchgrevink to return and explore Antarctica more fully.

Borchgrevink was born in Christiania (now known as Oslo) in 1864 to a Norwegian father and an English mother. He emigrated to Australia in 1888 where he had worked with survey teams in the bush and as a teacher before joining the Antarctic. Little is known of his early years, during which he claims to have attended Christiania University, but it is clear Borchgrevink was not a man who was easily deterred. Having failed to raise funding for his proposed Antarctic expedition in Australia, Borchgrevink headed to England to continue his quest. There he met with rejection after rejection until, in 1897, he met the wealthy magazine publisher, Sir George Newnes, who granted him some £40,000 towards the expedition.

![]()

![]()