When the Aurora returned to Cape Evans, now surrounded by open water, the men were shocked to discover that most of the fuel had disappeared or was buried. It was assumed that this had been washed away by a tidal wave. The Aurora was positioned a short distance offshore and by late April, was held by two bow anchors, and by wire hawsers and a mooring chain to two large anchors embedded in the beach. These had been rafted ashore on a platform to which old petrol drums were fitted. The intention was to winter the ship just off shore with most of the party on board, as had been done with the Discovery in 1902 and 1903.

A small science party was to remain ashore at the hut and mattresses, rugs, books and cutlery were taken ashore. Apart from some stores, very little equipment and no clothing was taken ashore. Parts of the acetylene plant were taken to the ship and modified, and the stove in the wardroom was also modified to burn blubber; the suggestion was made to use the stable wall to erect a bulkhead and halve the size of the hut, although this was never done. On two occasions the Aurora broke away from her anchors in bad weather but was able to return to the mooring site. The sea gradually refroze, but on 6 May a blizzard blew the ship out into the sound and it was unable to get back to Cape Evans. This left ten men stranded on Ross Island, six at Hut Point and four at Cape Evans. The badly damaged Aurora drifted up the Ross Sea and was lucky to make it back to Port Chalmers in New Zealand.

Eventually, the two shore parties were reunited at Cape Evans on 2 June 1915, although there was great concern for the men on the ship, which they thought had been lost with all hands. During winter, some scientific observations were carried out and preparations were made for the spring and summer sledging. The men decided that their second planned trip to cache supplies for Shackleton must be completed despite their setbacks and lack of supplies, and they prepared as best they could during the remainder of the harsh polar winter. Joyce and Wild, both seamen with wide experience, then set to and began to overhaul old primus stoves and to improvise clothing from an old tent. Old Scott expedition sleeping bags became fur boots and dirty clothing was washed in petrol. A ‘billiard game’ found on a roof beam provided entertainment, and in May a heavy snow fall covered “unsightly rubbish and piles of boxes”.

In August, the sea-ice was sufficiently firm to enable a party to visit Shackleton’s hut at Cape Royds. Here, they foraged for matches, soap and other necessities. Seals were killed for fuel and for food for the party. Of the six dogs still living after the autumn sledging journey, only four were healthy and the two sick dogs died that winter.

In September, stores were sledged to Hut Point and the motor sledge was dragged back to Cape Evans, where part of the stable wall was dismantled to provide a workshop and garage. A new clutch was made, but the machine was only trialled briefly before being pushed back outside, where it remained for another 40 years.

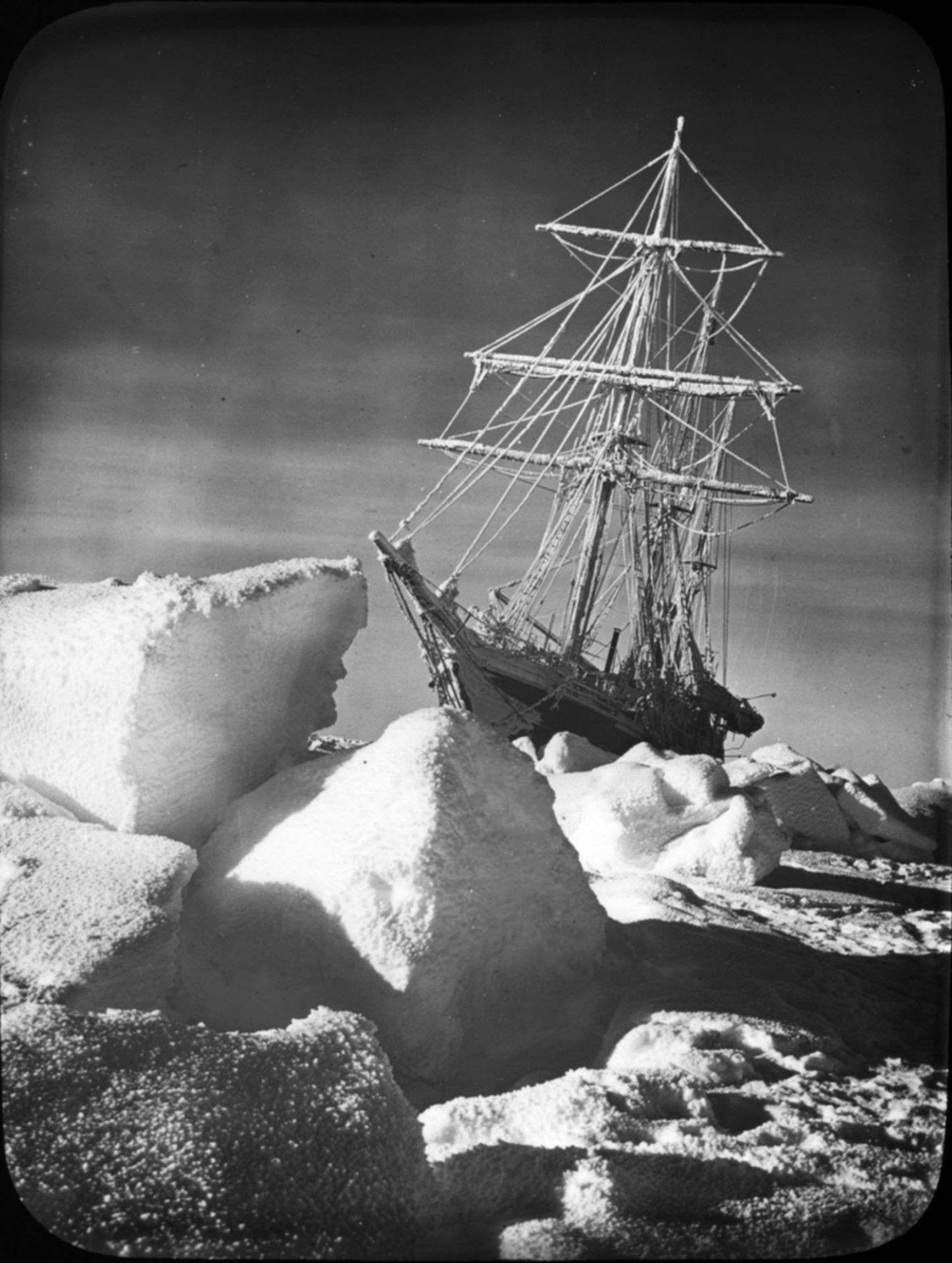

In October, nine members of the Ross Sea Party set off in teams of three with their remaining dogs on a planned five-month sledge journey, this time intending to lay caches all the way to Mount Hope at 83º 37’ south. They had no way of knowing that, on the other side of the continent, Shackleton and his crew had not even begun their journey and at the end of the month would abandon the ice-locked Endurance which was crushed and sank.

Once again, the sledging parties were overloaded and they had trouble with the primus stoves they had salvaged from the hut. Despite their troubles, the final depot was laid at Mount Hope on 26 January, but their return journey was not without a price. Two of the men were suffering from scurvy and had to be hauled on sledges. On 9 March, Reverend Arnold Spencer-Smith died of scurvy and was buried on the Ross Ice Shelf. By then, all of the men had scurvy but, fortunately, the comparative safety of Hut Point was reached just two days later.

Their troubles were far from over, however. Their ship was gone and they were forced to live primarily off seal meat while staying in the frigid hut. In the words of expedition physicist Dick Richards:

“The hut may have been a dark cheerless place but to us it represented security. We lived the life of troglodytes. We slept in our clothes in old sleeping bags which rested on planks raised above the floor by wooden provision cases.”

They spent the next seven weeks huddled in temperatures only slightly above freezing, living on meagre rations. On 8 May, Captain Aeneas Mackintosh and Victor Hayward decided to walk to the more comfortable hut at Cape Evans despite the fact that it was too early in the season for the sea-ice to be solid. Two days later, a search party found evidence that the pair had been carried out to sea on an ice floe. Meanwhile, on the opposite side of the continent, Shackleton was sailing in the James Caird to South Georgia Island where the worst of his epic endeavour would end after a gruelling trek across the island.

It was not until 15 July that Joyce, Richards and Wild were able to cross the sea-ice safely from Hut Point, rejoining Stevens, Jack, Gaze and Cope at Cape Evans. They had subsisted on nothing but seal meat since the middle of March. The interior of the hut was soon blackened with soot from seal blubber. An inventory of stores was made and, in the months ahead, perhaps anticipating a third winter, seal blubber was stockpiled in the annex and 2,400 Adélie penguin eggs were collected at Cape Royds.

With the return of summer the men hoped for relief and on 10 January 1917 Richards spotted a ship. The Aurora had been repaired at Port Chalmers and the relief expedition mounted by the governments of Britain, Australia and New Zealand, with Shackleton as a passenger, returning for the survivors of the Ross Sea Party.

The Ross Sea Party had demonstrated a tremendous level of courage and commitment to their task, which ultimately proved to be in vain. A cross to the memory of Mackintosh, Hayward and Spencer-Smith was erected on Wind Vane Hill. An inscription was not added to the cross although a draft was found in Cape Evans in 1960–61.

The Cape Evans hut was closed up, marking the end of the heroic era of exploration in the Ross Sea region; it was not to be entered again for 30 years.

![]()

![]()