Expedition Blog – Daniel Bornstein, Ross Sea 2025

A Childhood Rememberance

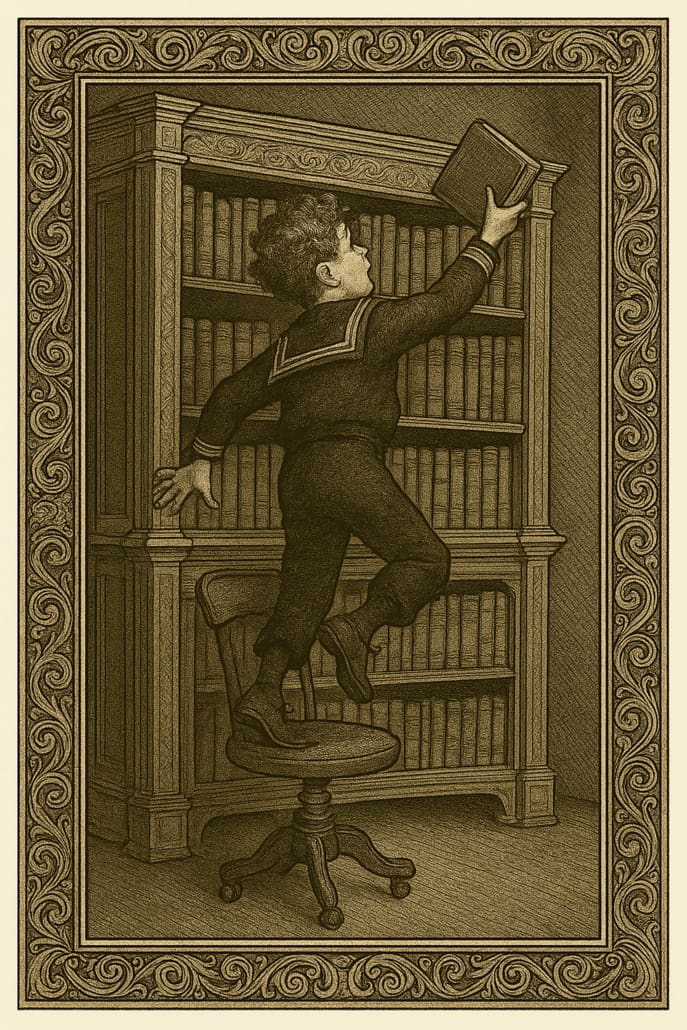

Even today, through the nebulous fog of boyhood memories, I can distinctly recall the day I managed to reach to the top shelf of my grandparent’s bookcase and retrieve the prettiest book. With a fearlessness seen only in young adventurers (and perhaps a few polar explorers), I balanced precariously upon a rickety swivel chair, flicked the red cloth-bound codex out by its ancient silk headband, grasped the volume in my grubby mitts and beheld the lettering in shimmering gilt: The Count of Monte Cristo.

At a glance, exquisitely engraved plates tantalised my young imagination with scenes of roguish betrayal, discovery of ancient papal treasures and the thrill of Parisian political scandals: I knew then that this book was to occupy me for some months.

Monsieur Dumas did not disappoint. With each ensuing day I became more invested in the fickle fortunes and vengeful obsessions of Edmond Dantes, all the time giving little regard to the toll I was exacting upon the fragile case-bound codex that I so mercilessly tossed into the yawning depths of my schoolbag. Cold and damp as an oubliette in the Château d’If, in lieu of a learned Abbé there was only the company of broken pencils, leaky drink bottles and smooshed bananas.

When finally the revenge of Dantes was played out, Dumas’ masterpiece was a sorry sight. My Master’s in Cultural Materials Conservation has given me the words to describe the damage wrought by my negligence, but years of compounded shame have given me the self-consciousness to suppress their publication. For years, I carried this shame, a secret chip upon my shoulder as I forged my path in the conservator’s trade. Then one day, more than twenty years after, the Antarctic Heritage Trust gave me an opportunity to atone.

Monte Cristo, Revisited

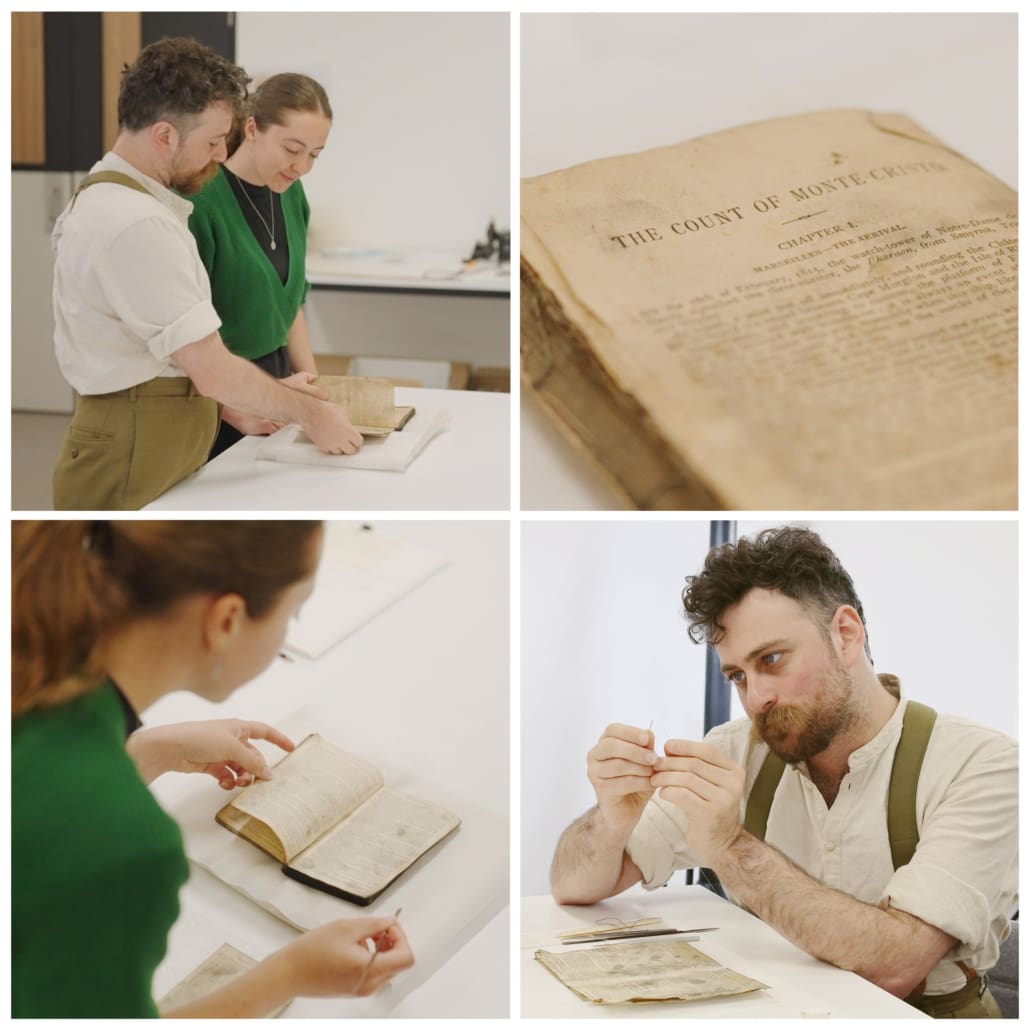

I was, to say the least, intrigued when Inspiring Explorers™ Programme Manager Mike Barber asked if I could stay on after our team-building weekend to undertake an object treatment with polar conservation superstar and Antarctic Heritage Trust Heritage Manager Lizzie Meek, and fellow Inspiring Explorer (IE) Louise Piggin. Lou and I, along with the inimitable Lucy Hayes-Stevenson (Heritage Architect extraordinaire) were the three lucky young heritage professionals selected for the 2025 Inspiring Explorers Expedition™ team we’ve all come to know and love.

When the Team Building Weekend rolled around, and the members of our dream-team met and got to know one another, Mike explained that, fine weather prevailing, it was envisaged we were to be counted amongst the handful of people lucky enough to return an artefact to one of the historic huts. When I learned this object, which Lou and I were soon to treat, was to be a copy of The Count of Monte Cristo, well it seemed to be providence.

My personal love of the novel aside, the object is an interesting one. To give a brief history, this copy of The Count of Monte Cristo is associated with ‘Discovery’ hut at Hut Point. The hut was originally constructed by Robert Falcon Scott’s crew on the 1901–1904 National Antarctic Expedition. Generally known as the Discovery Expedition (after their ship, the Discovery), the site was strategically chosen for its location, within spitting distance (≈ 1350 km) of the South Pole. This spot was more or less the closest point which could be reached by ship that summer, and was also by all accounts a lovely spot for ballooning. It is unclear who brought the artefact, but it may have been associated with any of the multitude of brave explorers who called the ‘Disco’ hut home during the ‘Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration’ (1898-1922), most recently Shackleton’s fated Ross Sea Party. The Count of Monte Cristo appears in a few 1960s inventories taken at Hut Point, and then disappears from records until (we now know) it was eventually gifted as a school prize to a lucky young Kiwi, c.1965.

While today this sort of Indiana Jones style souveniring of artefacts from historic sites falls cleanly under the jurisdiction of ‘looting’, it must be remembered that back in the great heroic age this methodology was, more or less, the way to legitimately populate a museum. It is worth noting also, that the book is thought to have been discovered outside the hut in the sweepings, so in this instance we can say with reasonable confidence that, had it not been taken then, we would likely not have it today. Complex ethical discussions aside, we are very grateful the previous custodian, in their doting years, thought to place it in the care of Antarctic Heritage Trust, and I personally am very grateful that AHT, in their great trust and magnanimity, thought to place it in the IE team’s care for its triumphal return to Discovery hut.

History on Ice

Since I was engaged in my capacity as a heritage professional, I feel it would be remiss of me not to dwell somewhat on the ethical and professional considerations surrounding this kind of work. To begin with, it is worth taking a moment to note that I have discussed the ‘return’ of an object to the Ice, rather than a ‘repatriation’, which is a term which carries its own complexities I will not unpack here. Even simply returning artefacts to their ‘natural home’ in the huts, however, is not such a straightforward prospect.

There is little doubt the huts in the Ross Sea region are of immense cultural importance to the story of humans in Antarctica. But the approach to the care of this legacy within the ethical guidelines of the conservation profession can be a little curly. The discussion has been summed up by Janet Hughes in the abstract to her very illuminating paper in the Polar Record, ‘Ten myths about the preservation of historic sites in Antarctica and some implications for Mawson’s huts at Cape Denison’:

There has been considerable debate in Australia and New Zealand about how historic Antarctic buildings should be preserved. Proposed preservation methods have covered a wide range from dismantling and repatriation to a museum, re-cladding with new timber, insertion of vapour barriers inside walls to exclude ice ingress, covering buildings with a dome, and, at the other end of the spectrum of views, minimal intervention. The preservation of artefacts has also been an issue, particularly concerning whether artefacts can be effectively preserved in Antarctica or whether it is necessary to treat and store them at museums outside Antarctica. It is important to encourage consideration of all appropriate means of preservation, but it is particularly important that the causes of deterioration are understood (that is, correct diagnosis) before prescribing treatment (Hughes, 2000).

The Trust’s meaningful engagement with, and profound contribution to this discussion is demonstrable in the insanely extensive and downright impressive works undertaken on their behalf by more than 100 heritage professionals from all over the world who have worked with them on the Ross Sea Heritage Restoration Project (RSHRP) since 2006.

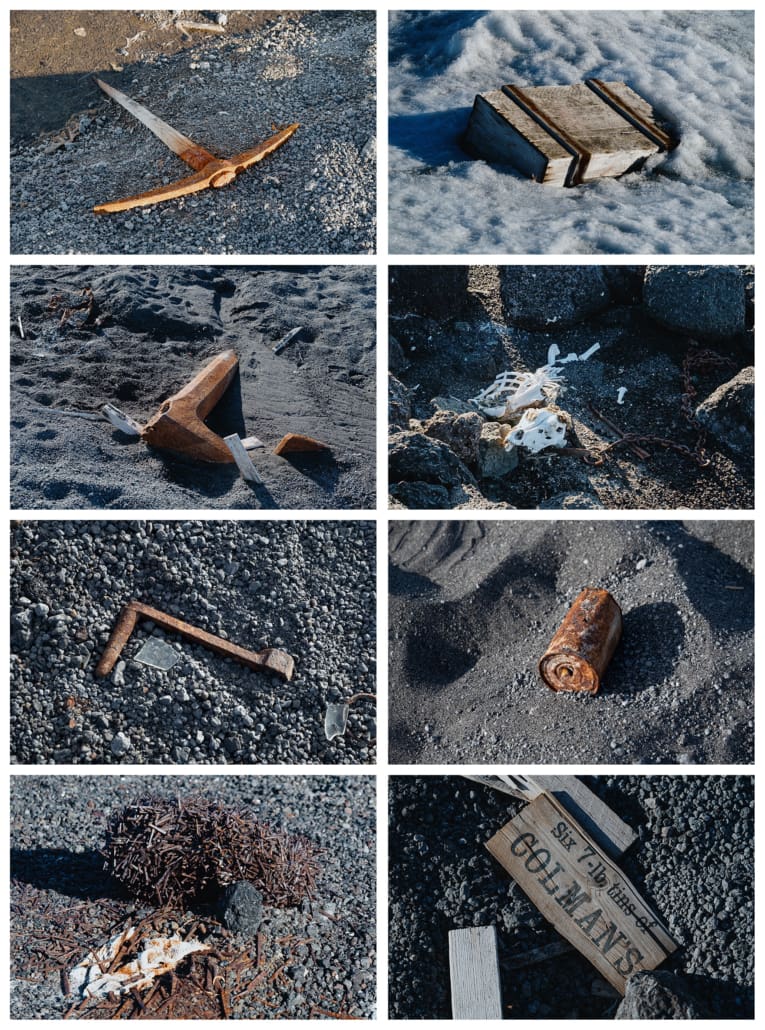

For example, having now seen first-hand their extraordinary work at Scott’s Cape Evans Terra Nova Hut it is clear the approach taken is a dynamic melange of all of those discussed above. The extensive conservation work on the huts and the 20,000 or so associated artefacts, both in situ and at their makeshift labs at Scott Base and Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, firmly answers the question of whether objects can be preserved in an environment as extreme as Antarctica. In the spirit of differentiating ‘can’ from ‘should’, having now seen the state of the beach at Cape Evans in the thaw, strewn with the detritus of cold and bored men from times gone by, it is clear the Trust has also taken a considered approach regarding what not to do. While this is in keeping with the conservation principle of ‘minimal intervention’, the documentation and ongoing monitoring of everything brought to site by human hands means every case is an ongoing discussion.

Conservators like current Heritage Manager, Lizzie Meek, and former Ross Sea Heritage Restoration Project Manager, Al Fastier, are able to develop complex, pragmatic and responsible decision-making pathways by referring to the exemplary peer-reviewed Conservation Management Plans prepared for each site by a range of allied professionals. But these plans need to be continually reassessed and revisited with a view to the future, so the work is never really done. Having now visited Cape Evans on a nice clear day, and seen the surprising proximity of the hut to the waves lapping gently against the scoria it sits upon, I am sure with rising sea levels I will be reading discussions about hut relocation within the span of my career.

While all conservation project planning should leave a little room for force majeure (or perhaps damnum fatale), when there’s a 24-month delivery time quoted on your materials and the freight costs are written with zeros on both sides of a comma you’d better make damn sure your scoping is rock-solid.

Authenticity, and the ‘spirit of place’

There is an old cliché that once you become a conservator you can only see objects displayed in galleries from oblique angles. While it is true, walking through the huts I was perpetually cognisant of choices made in curatorial presentation and interpretation, of lux and material compatibility considerations relating to object placements, and indeed of any stitch I may have noticed out of place. I think it is worth pointing out though, that in every case my impression was that the utmost attention has been paid to maintaining the overall interpretive value of the object and site. As pointed out by all who have visited the huts, despite (what in some cases has been) extensive interventive work, the hand of the conservator is never perceived at first glance. The net effect when walking into these spaces is always the extraordinary sense it has been frozen in time, that the fellas’ have just stepped out to have a smoke, or hunt seals to fuel their blubber stove, and will return at any moment over the threshold you just crossed.

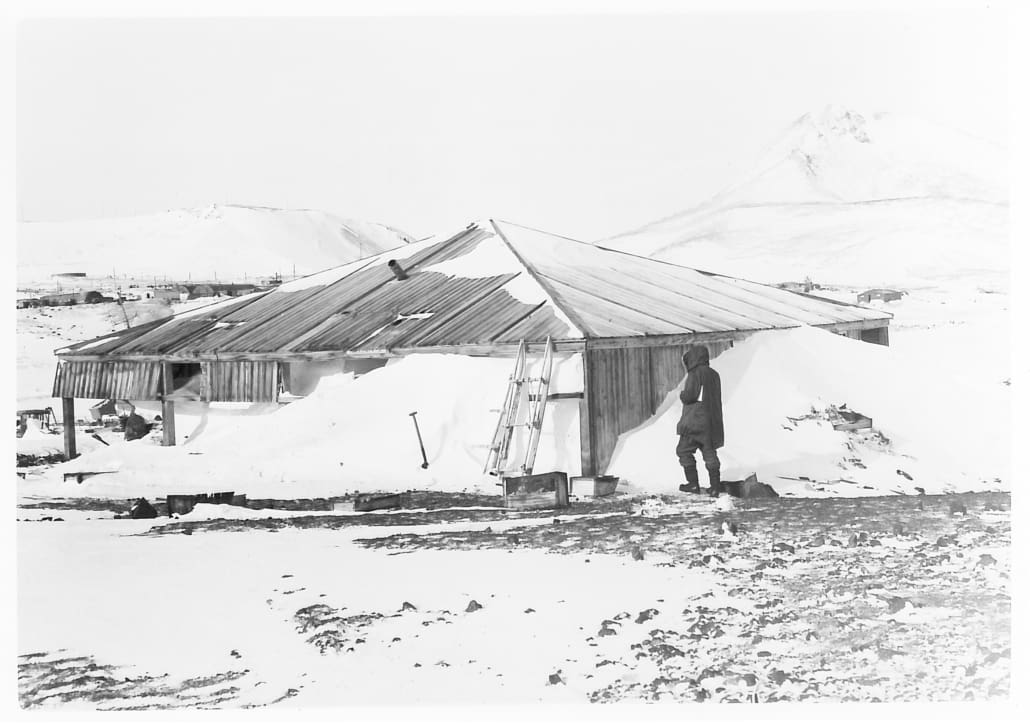

The uncanniness of this feeling cannot be overstated. It is impossible, in visiting Antarctica, not to think about the environment and the archetype of uninhabitability it represents. Antarctica’s existence is a defiance of the human instinct toward perpetual expansion which is, in itself, an insubordination of the natural order of animal savagery perpetrated by us in pursuit of increased human comfort. In a perverted way, it felt as though humanity was winning on our first Antarctic landing at Cape Adare, where we sweltered in our hard weather gear on an unprecedented calm, sunny, 6° day. Nature got us back at Hut Point, where we were lulled by prior landings into a false sense of comfort and then hammered by -30° wind chill. Stepping out of the howling katabatic winds and into Discovery hut was to be enveloped in perfect stillness, intimate calmness, a reprieve from the violence of the wind and weather.

Opinions differ regarding the ambitions and dreams of the people who built these huts, just as they do for (and by) those who maintain them today. Similarly, everyone who visits these places makes their own meaning of glacial melt, warming climate, avian mortality, and the million other stinging questions which are deeply personal to them. Everyone enters their own hut, finds their own meaning and is guided by the spirit which dwells in these timeless cathedrals of human resilience, shelter and comfort. The spirit of the hut is the story of its history, and its future. It is its cultural meaning, and authenticity. The intertwining of this spirit with new narratives renews the cultural relevance of the Heroic Age legends, justifies their ongoing care, and fosters their promotion for new audiences.

It is a privilege to visit these huts, by any definition. This will never change, given their being situated in one of the world’s least accessible areas is integral to their cultural meaning. This question of accessibility, in my opinion, is where AHT undertakes some of their most interesting work because it is here, where one begins to consider not only the depth of their audience’s engagement but also the breadth, that their outreach programmes really begin to make sense.

What it’s all about

To a conservator, the question of “why should we conserve these huts?” seems absurd, because of course we should conserve these huts. But the work is expensive, and difficult, and even dangerous, and so it is not only reasonable, but also actually quite important to question the value and meaning of the project. For me, the opportunity to participate in something like the Inspiring Explorers™ programme was an incredible affirmation of the value good conservation work can bring. What’s more, it answered the question of why we do what we do in ways I had not considered.

The Count of Monte Cristo is an important part of the Discovery hut story. The scores of blubbery smears which mark each page demonstrate its immense value to the men, highlighting their favourite passages in clusters of sooty fingerprints. It is the only extant artefact which doesn’t immediately relate to the occupants’ work or survival, and therefore the only object which effectively speaks to the passing of the uncountable hours of anxious waiting and uncertainty which was their reality. But it also tells a story of their leisure time, and perhaps of camaraderie and polar intimacy, if one indulges a little vignette of bedtime stories read to one another by blubber-light. One can imagine them relating to Edmond Dantes, the young mariner who finds transformation and self-betterment in the endless suffering of complete isolation. Likewise, in bringing this book back to what feels like its natural home, where these men would have huddled together to thaw their way into their reindeer-fur sleeping bags on the platform by the stove, we have become a part of its story, and it of ours.

It is interesting to see how we all make sense of things differently. Getting to know these stories, places and objects through the eyes of my team, and the amazing insights and observations each of them brought, was a pleasure and privilege for me. It has been humbling and gratifying to share my own experiences and understandings, and to deepen those understandings with what I have been lucky enough to learn from my shipmates on our journey.

I can already see the changes in everyone, and in myself, personally and professionally. In seeing how our team have individually and collectively adapted the stories of the Antarctic heroic age. I can also see now that the Inspiring Explorers™ programme is guiding the AHT as much as the AHT is inspiring the next generation of young explorers.

And I guess, that’s what it’s all about

On the one hand there is the good ol’ fashioned Ross Sea Heritage Restoration Project conservation work happening on the Ice. Representing a gold standard in conservation project management and execution, these works are coordinated by an astoundingly small team of incredibly competent people. On the other, there is this extraordinary outreach work, not only with the Trust’s Inspiring Explorers Expeditions™, but also in their Education programme, the digital heritage projects, the media relations and even the commercial partnerships and product launch ventures. The ripple effects of these projects are seen through many cultural layers, and are something every heritage project should aspire to create. The countless smiles on young Kiwi faces attest these are the projects which make history meaningful; this is how you harness the power of Antarctica to improve the world, even for people that will never visit it.

For my own part, to meet the people building and running the AHT machine is an inspiring thing. It’s been great to be on the ground and see the raw materials from which Communications and Engagement Manager, Anna Clare and her comms team weave magic, or to watch Inspiring Explorers™ Programme Manager, Mike Barber change lives and help us change each other’s lives in real-time. To be mentored in the treatment and return of an object by the likes of Heritage Manager, Lizzie Meek, or to be guided through the huts by our ol’ shipmate and former Ross Sea Heritage Restoration Project Manager, ‘Fast Al’ Fastier, is for somebody in my profession akin to hearing Antonio Stradivari play a sonata in his parlour. I am excited to see what becomes of the huts in the coming years (in particular Cape Adare!), and I am just as excited to see what is next on the journeys of my IE family. I can say earnestly, and without exaggeration, this trip has been a highlight of my career, and of my life to date.

Finally, in recognition of my debt repaid to the memory of Alexandre Dumas, I leave my IE family with the final adieu of the Count himself:

Live, then, and be happy, beloved children of my heart, and never forget that until the day when God shall deign to reveal the future to man, all human wisdom is summed up in these two words,—‘Wait and hope.’

The Trust extends sincere thanks to our Inspiring Explorers™ Fund donors including Inspiring Explorers Expedition™ Partner Heritage Expeditions and supporter Cheshire Architects for making this journey possible.

Hyperlinks:

- ‘We’ve all come to know and love’: https://inspiringexplorers.co.nz/ross-sea/expedition-details/expedition-team/

- ‘The ‘Discovery’ hut at Hut Point’: https://inspiringexplorers.co.nz/ross-sea/history/scotts-discovery-hut-hut-point/

- ‘A lovely spot for ballooning’: https://doi.org/10.1017/S2398187300146006

- ‘Shackleton’s fated Ross Sea Party’: https://archive.org/details/cu31924032382529/page/244/

- ‘Hughes, 2000’: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247400016223

- ‘Extraordinary work at the Cape Evans (‘Terra Nova’) Hut’: https://inspiringexplorers.co.nz/ross-sea/history/scotts-terra-nova-hut-cape-evans/

- ‘The state of the beach at Cape Evans’: https://doi.org/10.26301/fexy-pm96

- ‘The final adieu of the count himself’: https://archive.org/details/countofmontecris00duma_10/page/479/