Sir Edmund Hillary on a Ferguson tractor leaving Depot 480 in December 1957 on his way to the South Pole.

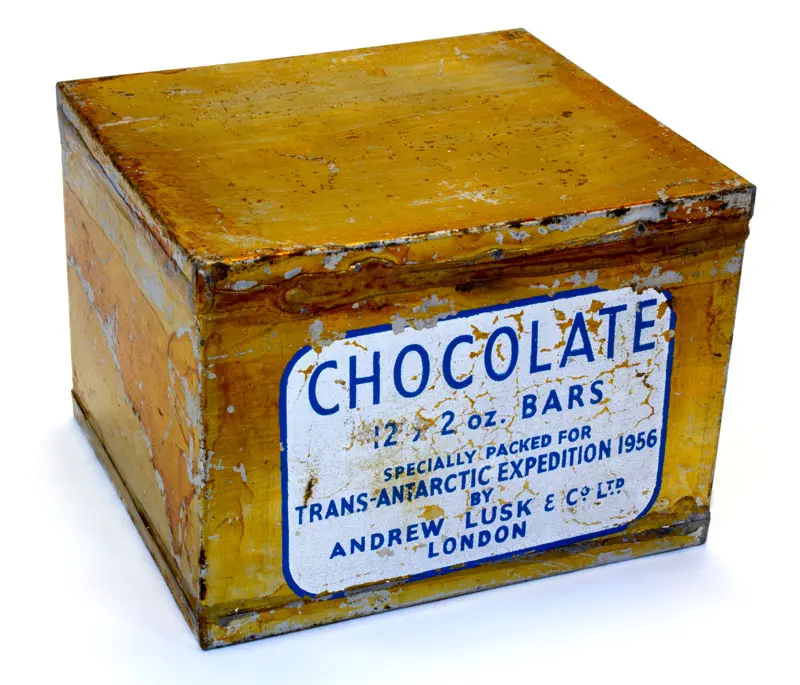

Chocolate bars from the Trans-Antarctic Expedition.

Two teams

This trans-continental expedition was under the overall command of the British explorer Dr (later Sir) Vivian Fuchs FRS, a geologist who had studied at Cambridge. There were 12 men in the Crossing Party, travelling in three Sno-Cats, two Weasels and an adapted Muskreg tractor.

The Ross Sea Party was led by Sir Edmund Hillary. The end point of the crossing was to be Scott Base. Fuchs had requested that New Zealand establish a group that would construct the base at McMurdo Sound and lay food and fuel depots up the Skelton Glacier and across the Polar Plateau towards the South Pole.

Both parties hauled large quantities of supplies overland, but they also had light aircraft supporting them with reconnaissance and supplies. Along with exploration, scientific research was an important aspect of the expedition.

The New Zealand Government initially committed £50,000 towards the expedition but it was to cost much more than that and fund-raising committees were set up around the country. From major corporates to school children, New Zealanders enthusiastically got behind this tremendous adventure.

Some sponsorship was in kind rather than cash – for example, Cadburys made sure there were chocolate and biscuits, and Dominion Breweries supplied beer, though many of the bottles cracked from the cold before they could be stored in the warmth of the hut.

Sir Edmund Hillary on a tractor bound for Cape Crozier.

Spring 1957

By late August the sun started to reappear, days began to lengthen and it was possible to start working out in the field. Sir Ed and his party were to set off for the Polar Plateau to set up the depots of supplies for Fuchs’ TAE Crossing Party.

There was a lot of doubt expressed about Sir Ed’s plan to use Fergusson tractors, each of which would be towing a sledge with 1.5 tonnes of supplies.

But seven months earlier they had done a test run to Cape Crozier, which revealed what they needed to modify to successfully tackle the longer journey to lay supply depots for Fuchs.

Don’t try this at home!

Returning to Scott Base from Cape Crozier the fuel in one of the tractors kept freezing. Mechanic Jim Bates, and radio technician Peter Mulgrew took extreme action.

“Lighting blowtorches, they carefully heated the fuel tank and fuel line just enough to get things back to a fluid state and the tractor moving again. Hillary and [Murray] Ellis, perhaps showing a sensible lack of solidarity in view of the risk of an explosion, stood well back!” (Hillary’s Antarctica, P.93)

D-Day – 14 October 1957

Sir Ed and the team set off on their mission. Three Fergusson tractors, a Weasel lent by the Americans, a wooden caboose designed and built by Sir Ed to provide some shelter and comfort – it got very cold on the driving seat of a tractor – and two dog teams. The Weasel was a dedicated snow vehicle with excellent traction in soft snow conditions. And the caboose was like a horsebox on skis towed behind the tractors or Weasel Each of the vehicles was hauling 1.5 tons of supplies. They were supported by planes dropping extra supplies, men and dogs at the Polar Plateau. There was a lot of goodwill for their journey but also considerable doubt that they could succeed in the tractors.

Tractor train about to move off on main journey south, October 1957.

Daunting challenges

On their journey to the Polar Plateau they would have to deal with winds that were so ferocious that the dog teams were blown off their feet.

“The men were forced to dig a separate hole in the ice for each dog to shelter in …” (Hillary’s Antarctica, P.86)

That was not all – freezing temperatures, blizzard conditions, flu, unexpected crevasses hidden by wind-blown snow, and the slope up to the Plateau so steep it felt like they were ‘like flies clinging to the wall.’ (Ed Hillary quoted in Hillary’s Antarctica, P.98).

But they made it!

“To see our four battered vehicles and the laden sledges at the Plateau Depot seemed to be the fulfilment of an impossible dream. I don’t think that ever before, even on the summit of Everest, had I felt a greater sense of achievement.” (Sir Ed Hillary)

Ayres preparing to leave Depot 480.

“I don’t think the English ever forgave me for that one.”

From the very beginning, Sir Ed had said that the New Zealand team should have enough food and fuel to enable them to drive to the South Pole if things went well. That idea was strongly opposed and he was expressly told he was not to attempt it.

After setting up the Polar Plateau Depot, Sir Ed and his team went on to set up two subsequent depots, D480 and D700 miles (1126 kilometres) from Scott Base. They’d had plenty of difficulties on the way but had made reasonable time and were in good shape.

The Crossing Party was making only slow progress towards the South Pole and Sir Ed began to wonder if Fuchs would complete his journey in time to catch the last ship out of McMurdo Sound in autumn.

At D700 the New Zealanders were now ‘only’ 550 miles (885 kilometres) from the South Pole, and they had enough fuel to get there (though with no reserves).

Hard to stop

Sir Ed Hillary sent a message to Fuchs to say that his group would attempt to travel to the South Pole. He was sent a radio message from the New Zealand Ross Sea Committee telling him he was not to proceed beyond D700. Sir Ed’s reaction was:

“If an explorer in the field always waited for permission from his committee at home then nothing would get done or it would be done too late. Time spent sitting around at depots was just time wasted. With a grunt I put the message aside …” (Hillary’s Antarctica, P.115)

Hell-bent for the Pole

Christmas Day 1957 was not neglected at D700 – salmon fishcakes, tinned peaches, hot cocoa and fruitcake accompanied by a tot of brandy. On Boxing Day Hillary sent the following message to Scott Base:

“We are heading hell-bent for the Pole, God willing and crevasses permitting.”

It was a controversial decision and the journey a difficult and slow one. At one point the ground conditions were so bad that the tractors couldn’t move forward in the deep snow. They made the decision to leave behind sledges, camping gear, 80 days rations and kerosene. It was a risky strategy but it paid off and with the lightened load they were able to move off again.

The party was very low in fuel and exhausted when they eventually saw a row of tiny black dots in the distance – the flags that marked the airstrip for the American base at the South Pole. They set up camp that night and radioed Scott Base with the news that they were in sight of the South Pole.

The next day, 4 January 1958, they covered the remaining 15 kilometres – they had reached their goal, and arrived to a very warm welcome. And their American friends knew just what they would enjoy most at that point:

“You’re probably hungry. Would you like a steak meal?”

Hillary and his team were the first people to complete an overland crossing in motorised transport to the South Pole.

The fallout

Not surprisingly, relations between Vivian Fuchs and Sir Ed Hillary were tense. They didn’t improve when Sir Ed suggested – because the Crossing Party was making slow progress – that Fuchs fly out from the South Pole and complete the crossing the next season. News of this proposal was also inadvertently sent out to media, which created a storm.

Fuchs not only dismissed the idea, he also advised Sir Ed that he would no longer need his assistance travelling from D700 to Scott Base.

Fuchs and his party arrived at the South Pole on 18 January 1958, and Hillary was there to meet them. Relations between the two men were improved, at least to the point where it was agreed that Sir Ed would join the Crossing Party at D700 to help guide them safely back to Scott Base.

Fair to say that it was not a pleasant journey. The Sno-Cat had only two seats in the cab upfront, so extra passengers had to sit in the back, to which Hillary was consigned. There was no insulation, heating or windows. These were the conditions under which Hillary spent much of that journey, only to be called out when Fuchs had lost his way.

TAE crossing party on completion of journey.

Sno-cats of the TAE crossing party arrive at Scott Base.

The first overland crossing

The Crossing Party arrived at Scott Base on 2 March 1958. It had taken 99 days to cross the continent – one less than Fuchs had estimated! – and they had covered 2158 miles (3473 kilometres).