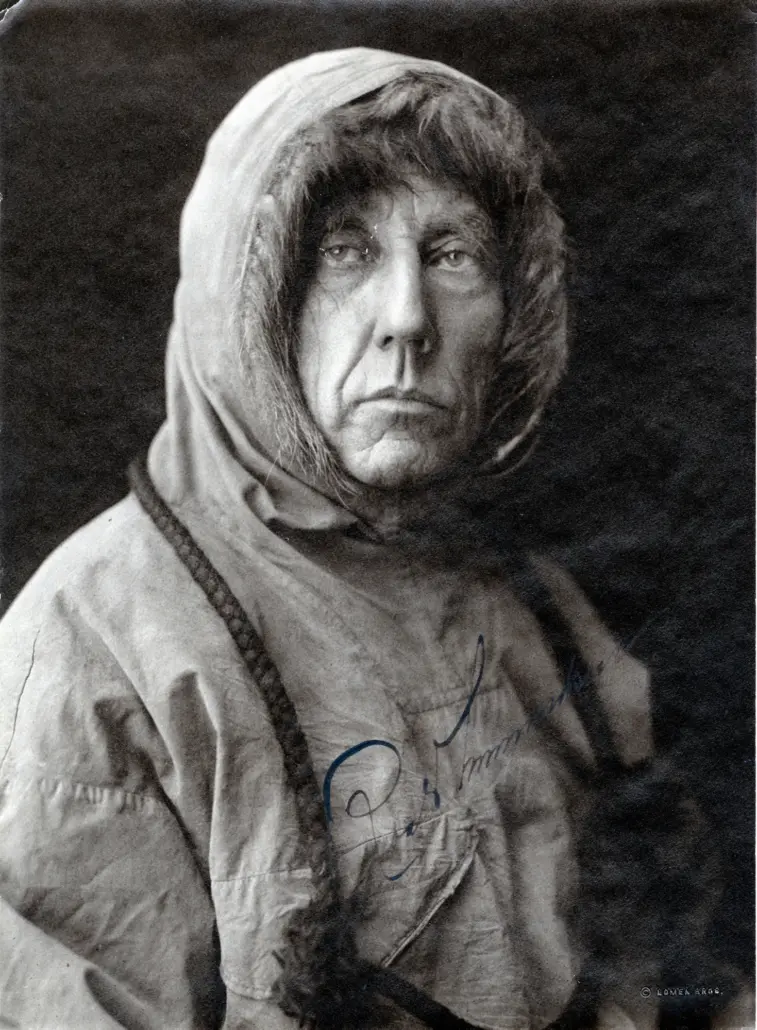

Roald Amundsen was a pioneering explorer who gained global fame during the heroic age of polar exploration for his Arctic and Antarctic expeditions. He and four comrades were the first people to ever reach the Geographic South Pole, on 14 December 1911, beating Captain Falcon Scott and his party by a mere 34 days in an epic, and infamous, ‘race to the Pole’.

Life and early expeditions

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen was born 150 years ago on July 16, 1872, in a small parish named Borge in Østfold, Norway, near Oslo. As a child he was fascinated by stories of adventure. His widowed mother wanted him to become a doctor, but after she died, when he was aged 21, he gave up studying medicine to pursue his dream and became a sailor instead.

Belgian Antarctic Expedition 1897–1899

He soon signed on for his first Antarctic expedition, as first mate on Adrien de Gerlache’s Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–1899. The goal of the expedition was to advance scientific and meteorological knowledge of the Antarctic region. The most significant geographical discovery made by the expedition was the discovery of the Gerlache Strait. However, it was beset with difficulties and the crew ended up trapped in the sea ice of the Bellinghausen Sea on 28 February 1898 unable to power the ship in any direction. Consequently, they became the first crew to winter over in the Antarctic region on board a ship.

During the miserable months that followed, the crew battled lack of supplies, morale and ill-health. Amundsen and fellow crew member, experienced explorer Dr Frederick Albert Cook, who later led the first team to reach the North Pole, took over command of the ship, insisting the men eat seal and penguin meat as a way to ward off the scurvy that had so weakened them. Eventually, the men cleared a path in the ice, enough to power the engine, and on March 14 1899, the Belgian Antarctic Expedition finally emerged from the pack ice.

The North West Passage 1903–1906

The experience did not prevent Amundsen from swiftly signing up to his next adventure, this time as captain of a six-man crew aboard the sloop, Gjoa, with his goal to reach the Magnetic North Pole.

Amundsen was again forced to winter over, this time in the harsh Arctic climate near King William Island, for two winters. During this time Amundsen unsuccessfully attempted to reach the Magnetic North Pole, only to confirm it had moved since it was first sighted it in 1831.

This expedition became the first to successfully traverse the North West Passage, the sea route that connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans via the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America.

During the expedition, Amundsen connected with the local Inuit people, learning their survival techniques, and, importantly for his later South Pole expedition, came to understand the usefulness of huskies as a means of travel by sledge.

South Pole Fram Expedition 1910–1912

Now a veteran explorer, Amundsen had been planning an expedition to reach the Geographic North Pole, but was thwarted by news that the American, Robert Peary, had reportedly reached the Pole on 6 April 1909.

Undeterred, Amundsen simply switched his goal to the other end of the planet, pointing the Fram, earlier used by Fridtjof Nansen, to Antarctica and the South Pole.

He left Norway on 6 June 1910, keeping his intentions secret even from most of his crew until he reached Madeira where he sent a telegram to Captain Falcon Scott onboard the Terra Nova, then at Melbourne, Australia en route to Antarctica for his own attempt on the Pole: “Beg leave to inform you Fram proceeding Antarctic. Amundsen”.

The race was officially on. Scott worked hard not to convey his concern at Amundsen’s plans to his men and continued preparations for the expedition as they sailed to New Zealand, setting off from Lyttelton on 29 November 1910.

Amundsen reached the Bay of Whales, establishing a camp he named Framheim, from where he and his men laid a series of supply depots along the Ross Ice Shelf (then known as “the Great Ice Barrier”). The base was used between January 1911 – February 1912.

The party of five: Olav Bjaaland, Helmer Hanssen, Sverre Hassel, Oscar Wisting and Amundsen, set out for the Pole on October 19, with four sledges and 52 dogs. Using his hard-won experience to guide him, Amundsen and his men chose to wear Inuit-style attire, as opposed to the traditional woollen garb worn by Scott and his men.

The men had also made improvements to their sledges, reducing the weight and ensuring their supplies could be accessed with minimal exposure to the freezing temperatures. Well-trained Greenland dog teams were the key to their success, with Amundsen forming a plan to kill and eat the dogs along the route for additional sustenance to supplement their strategically limited supplies.

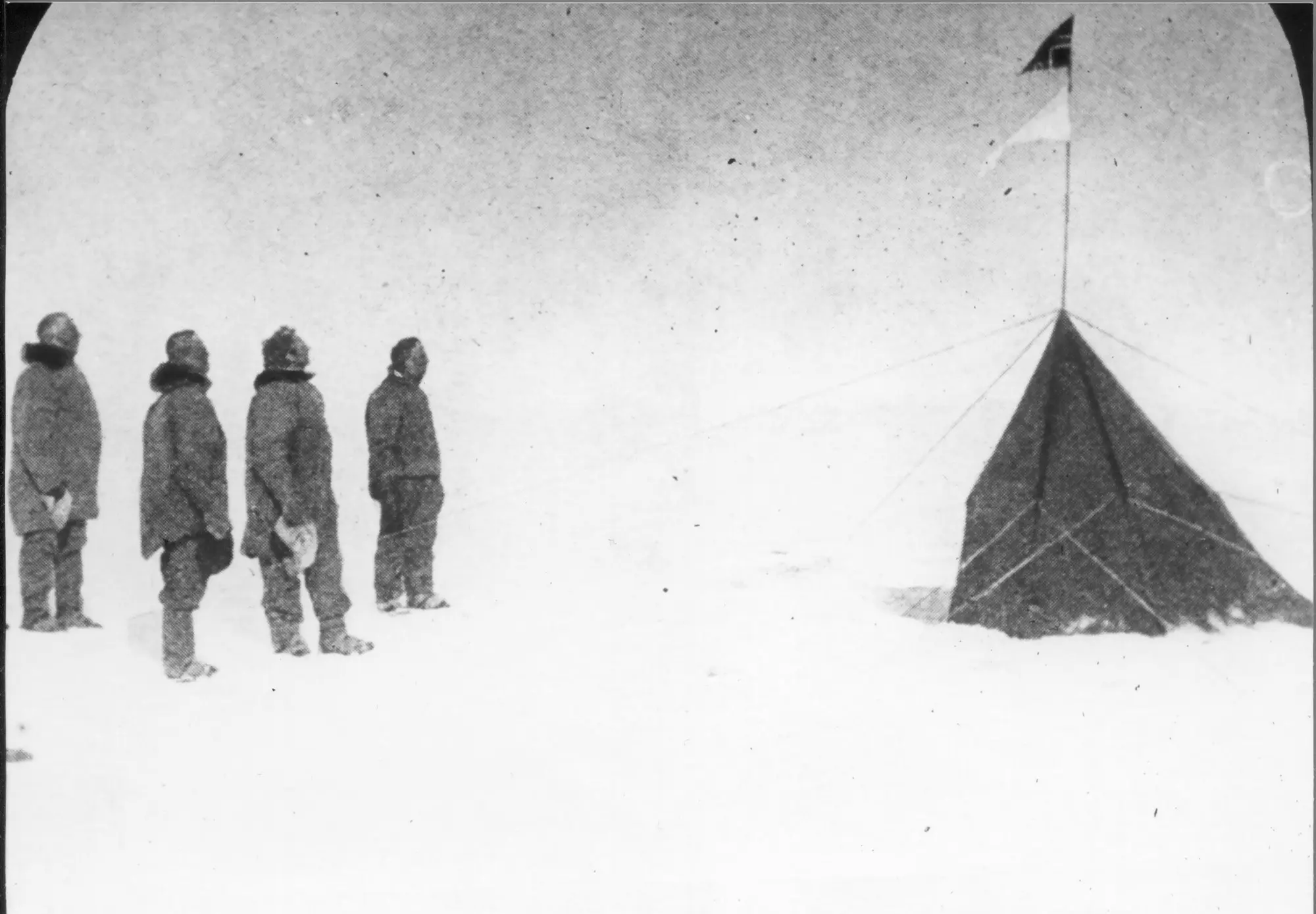

Amundsen chose a route via the the Axel Heiberg Glacier, and on 14 December 1911, Amundsen and his team reached the South Pole, claiming victory for Norway.

Meanwhile, Scott and his men battled across the Polar Plateau, finally reaching the South Pole on 17 January 1912. Waiting for them there was the small green tent that Amundsen and his team had left at the Pole some 35 days earlier. Scott and his team would perish on the return journey.

Amundsen and his men returned to Framheim on 25 January 1912, 99 days after their initial departure with 11 surviving dogs. On reaching Hobart, Australia, Amundsen announced the news to the world, on 7 March 1912.

North Pole Maud Expedition 1918–1925

Following his success in reaching the South Pole, despite controversy surrounding Scott’s death and the perception of deception on Amundsen’s part, Amundsen again set his sights on the North Pole, launching an expedition aboard the Maud in 1918.

During this expedition, although ultimately unable to reach the North Pole, Amundsen became just the second person in history to travel through the North East Passage, along Siberia’s Arctic coast from 1918 to 1920.

The Norge Flight 1926

On 12 May 1926, Amundsen, with a crew of 15, launched an aerial expedition aboard the airship Norge, flying over the Arctic Ocean and the North Pole, becoming the first party recognised to have achieved both feats.

Disappearance

Just two years later, on 18 June 1928, aged 55, Amundsen disappeared while carrying out a rescue mission on a plane in the Arctic. His remains have never been found.