Two Weeks at Cape Adare

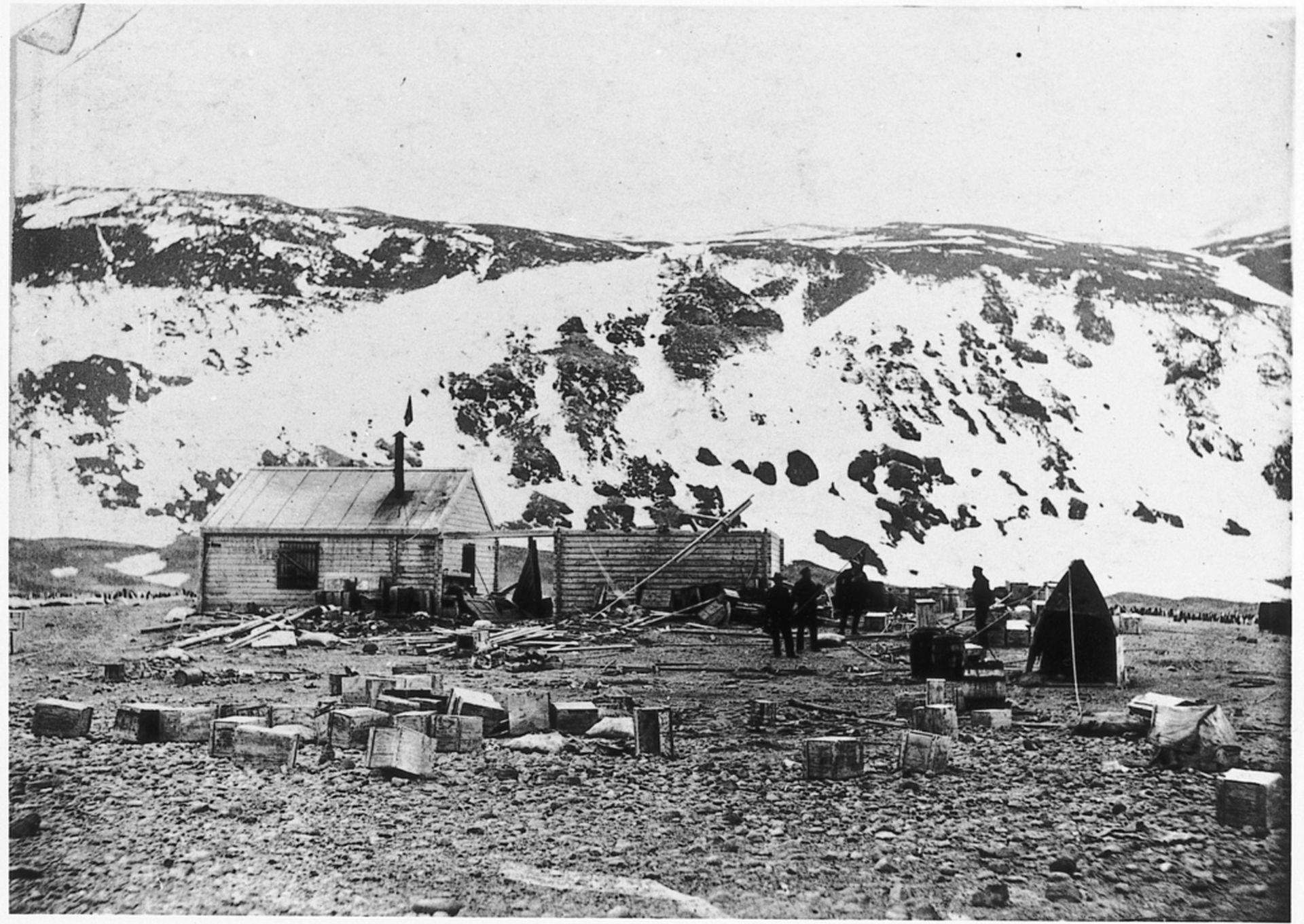

Inside an historic hut at one of the most remote places on earth, surrounded on all sides by the cries of hundreds of thousands of nesting Adelie penguins, Lizzie Meek, the Antarctic Heritage Trust’s Programme Manager – Artefact Conservation, completed the first task of one of the Trust’s most significant artefact conservation projects.

It was during a brief two-week window in the summer season of 2015–2016 that Lizzie Meek, along with Programme Manager Al Fastier and Torbyn Prytz from the Trust, carried out important conservation work at the buildings at Cape Adare, the first ever erected in the Antarctic. Today, Cape Adare remains the only place in the world where humanity’s first buildings survive on any continent. Two members of a Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation film crew accompanied the Trust team to Cape Adare and documented the project, later producing a documentary, Norway’s Forgotten Polar Hero, which has since screened twice on Norwegian national television.

While Al Fastier and Torbyn Prytz focused on repairs and maintenance of the building, Lizzie Meek was responsible for retrieving as many artefacts as she could from inside the main hut, cataloguing them, and carefully packing them ready to be transported back to New Zealand for conservation. “It was a pretty tight timeframe, but I managed to pull out close to 1500 artefacts from the main room and loft area. Some items were too fragile, hazardous, or too large to travel, but I packaged up all that I could,” says Lizzie.

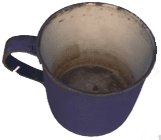

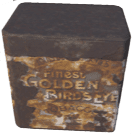

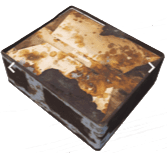

She says the task was a bit overwhelming to start with, given how much work there was to complete in a short time period, and with the condition of some of the objects being worse than she expected. However, her days were soon filled with a mixture of interest and pleasure in discovering so many unique objects from the heroic era of exploration, including clothing, tools, equipment, and food, left by members of Carsten Borchgrevink’s Southern Cross expedition in 1899 and the Northern Party of Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova expedition in 1911. Seven of these significant artefacts can now be viewed in the Antarctic 3D Artefacts experience on the Trust’s Augmented Reality App.

A typical day at Cape Adare started with the team post-breakfast meeting at 7.30am, which summarised each day’s work and health and safety protocols.

“We were hundreds of kilometres away from the nearest humans, so it was critical that we had two lots of communication with Scott Base each day. Although it is easy to feel like you are in the wilderness anywhere in the Antarctic, being such a long way from civilisation at Cape Adare was a very different feeling and absolutely wonderful.”

Each day, Lizzie worked methodically in the hut for nine hours, in three-hour blocks, which were broken by 45-minute breaks for hot food. “The condition of the interior of the hut wasn’t too bad, but it was still messy, dirty work and I was cold all the time. I had to work by lamplight as there was only a small amount of ambient light coming through one window.”

“Grovelling around” under old bunks in the hut, where Lizzie found an emergency stash of food including old cans of sardines, kippered herring, tea and other rations which were stuck fast, was one of her least favourite days on the job. But overall, it was fascinating and very rewarding work, she says.

As their two weeks at Cape Adare drew to a close, and a major storm approached, Torbyn Prtyz from the Trust spent a couple of days helping Lizzie to pack the last of the objects. As they went to weigh the crates ready to go on the helicopter, they realised that the group’s spring scale was missing. “In the end we spent quite a bit of time rigging up a home-made balance scale with a known weight on the other end. It worked just fine and was a good example of how you sometimes have to create something out of nothing in the Antarctic.”

The artefacts were transported to New Zealand under temporary permit, and the Trust’s team of conservators completed the conservation treatment programme at Canterbury Museum in July 2017. It was during this process that two of the most high-profile artefacts from Scott’s 1911 expedition were discovered – the well-preserved Huntly and Palmers’ fruitcake, and the beautiful 118-year-old watercolour painted by Dr Edward Wilson who died with Captain Robert Falcon Scott and three others on their return from the South Pole in 1912. “The fruitcake was well-disguised inside a rusty brown tin, and we had no way of knowing what was inside until the corrosion on it was removed,” says Lizzie.

While the discovery of the fruitcake and watercolour have rightly made headlines around the world, Lizzie says conservators find other parts of the conservation process equally as thrilling, for different reasons. “Things we aren’t expecting, like items or colours we haven’t seen before, or objects that have been handmade for a specific purpose, are things that conservators find really exciting.”

The artefacts are currently being stored in secure, monitored cool storage until they can be returned to Cape Adare at the completion of the building conservation work programme. This has been held up due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the challenges of returning to the remote site.

“The Trust is 100 per cent committed to bringing everything back together at the site and keeping it conserved.”

Lizzie has numerous personal highlights from her two weeks at Cape Adare. “I remember the feeling of tremendous relief and satisfaction of completing the task when all the crates filled with artefacts left Cape Adare, and knowing we were going to be able to give them conservation treatment. Working in a colony of a million penguins was another never-ending highlight. They are fascinating creatures to be around.”

It is a “simple but rewarding” life being a conservator, and Lizzie loves working at this point of the conservation “continuum” with the Trust. “The Antarctic sites are incredibly interesting and moving, and our work is for a whole community of people who want this to happen, who have given support, or donated money. Whether or not people can visit these buildings, they carry a resonance that has importance for so many people. They are connecting points for who we are, and why we are.”

How to access the app

The app is available to download for free from Google Play or the App Store.

The application is only available on surface tracking Augmented Reality compatible devices,

visit our store pages on your device to see if your device is compatible