The tins are from a box that was found under a bed at Cape Adare and came from Borchgrevink’s expedition.

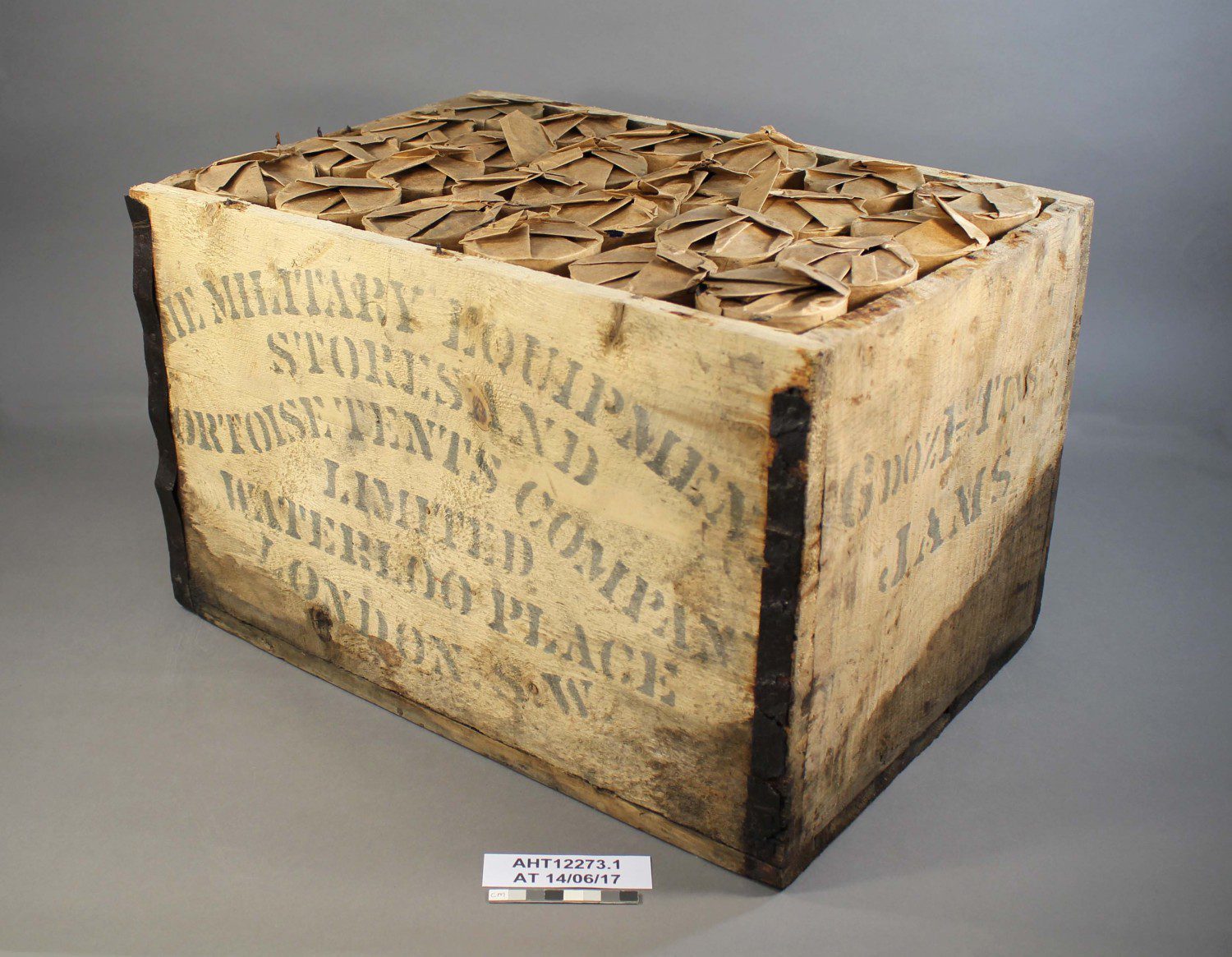

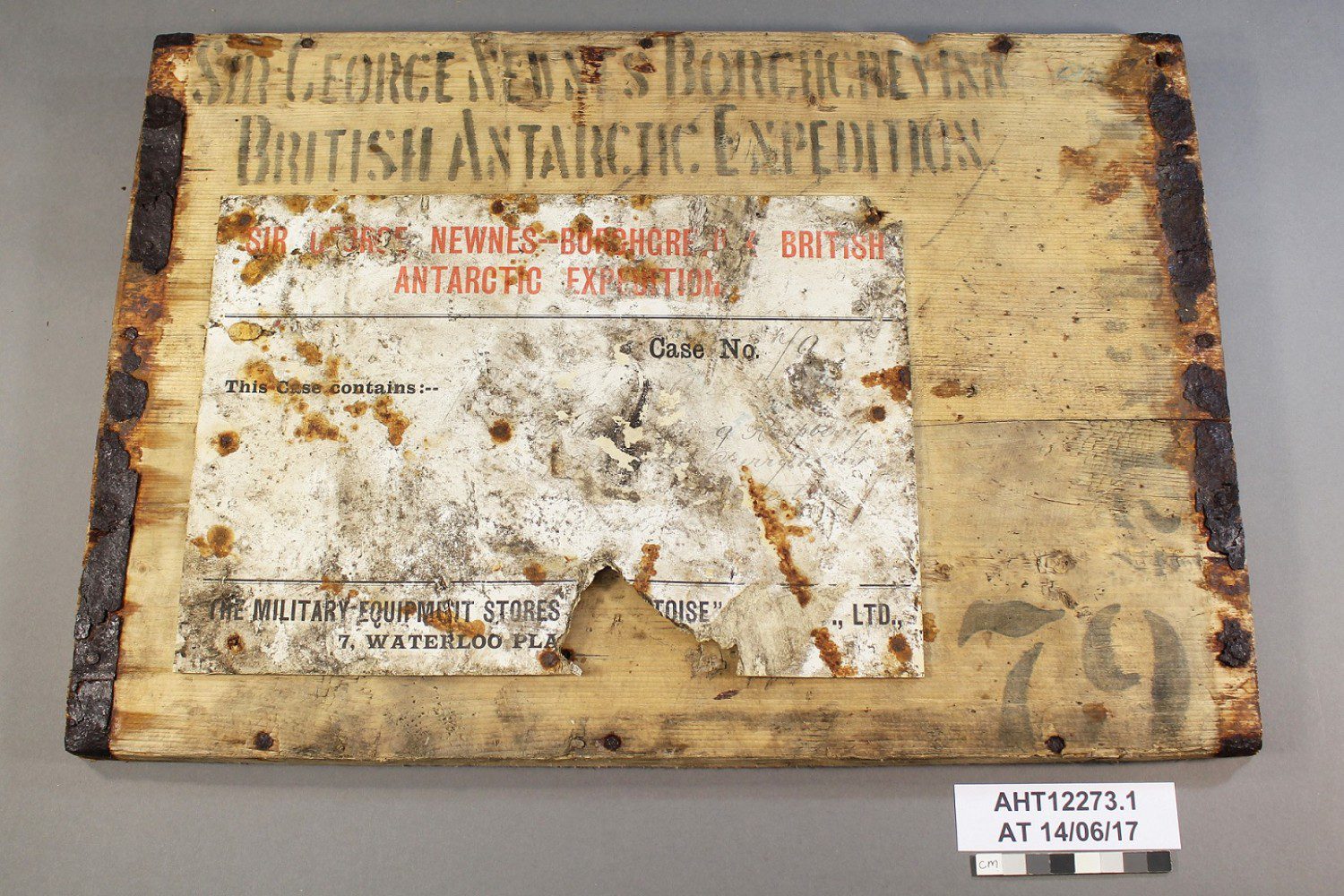

Before we opened the wooden box the label on the top and the stenciled information on the sides told us much of what we needed to know about the history of the case and what it contained – six dozen tins of jam.

The box had been found under a bed at Cape Adare and came from Borchgrevink’s 1898-1900 British Antarctic Expedition. Borchgrevink is named on the lid in bold stenciling, as is Sir George Newnes, the wealthy magazine publisher who donated funds for the expedition.

The box had never been opened but as it was oozing sticky, sugary syrup conservator Martin took the lid off and we were astonished to see that it looked as if the tins had been wrapped and packed in sawdust only the week before! Even the sawdust smelt fresh and piney.

Underneath their wrappers many of the tins were in very good condition, almost like new, and have a beautiful iridescent, blue hand-painted lacquer coating contrasting with the decorative red and gold labels – we all wished we still had tins like this.

Unpacking and counting the tins we noted the eight flavours – raspberry, gooseberry, cherry and currant, plum, apricot, raspberry and currant, strawberry and my favourite, black currant. Just visible on the paper label on the box lid was a hand-written record of the contents including 9 raspberry and 12 gooseberry, and indeed the tins inside tallied exactly with the list.

We opened those that were leaking and emptied out the jam, keeping samples for future research, before treating the tins. All the jams looked new, smelt sweet and delicious, and were gorgeous colours. The strawberry and black currant even had little berries in them. But no, however tempting they looked, we didn’t try them!

All the Heroic Era Antarctic expeditions had to take huge quantities of food supplies with them, and we know that Borchgrevink took enough to last him three years including a ton of marmalade, a ton of Irish butter, and five tons of bread. Their daily menus appear to have been quite repetitive and in his diary Borchgrevink notes that every day their lunch would include cocoa, cabin biscuits, jam and marmalade.

As with much of Borchgrevink’s supplies the jam came from The Military Equipment Stores and Tortoise Tents Company but unfortunately the company no longer exists.

Likewise, the manufacturer of the jam tins, C&E Morton, who specialized in preserved foods closed its last factory in Lowestoft in 1988. But in 1897 it had factories in Aberdeen, Falmouth and Millwall; and left a sporting legacy as it was the Morton’s tinsmiths who, in 1885, established the Millwall Football Club.

Jams from Cape Adare hut – there are seven varieties.

Jams in their original packaging found in the Cape Adare hut artefacts.

Examples of the jams found at Cape Adare hut.

![]()

![]()